It happens to almost every modern movie monster worth his salt. Freddy Krueger or Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers will start out a figure of terrifying evil, lurking in the shadows, often pursuing a plucky heroine. Then, by the third or fourth installment, the audience has become familiar with the ghoul in question, and maybe, on some level, starts to root for them and everything they promise: the unlikely resurrections, the elaborate kills, the obvious cues that the killer will be back in another sequel in a year or two.

It’s not that these monsters become less scary, though that does happen. More importantly, becoming the faces of their series turns them into de facto heroes. After all, it’s relatively rare for horror movie protagonists to recur in movie after movie; Scream is the exception that proves the rule, where a central trio of beloved characters survives across multiple films in part because the masked killer’s identity is intended as a surprise, rather than being the same old slasher. In most other horror series, it’s the monster that keeps the whole thing going.

Yet some horror movies have developed a counter-trope of sorts: the monster who takes the form of a young woman, often a teenager roiling with complicated emotions. While the most notable (and sequelized) contemporary movie monsters tend to be aloof slashers, unknowable and regularly masked, their humanity obscured or nonexistent, the Monster Girl is fueled by more obvious psychology. Not obvious in the sense of a tragic backstory, but in the sense of externalizing different combinations of the rage, confusion, and turmoil that are the byproducts of growing up. (Hence “girl,” rather than “woman”; though not every Monster Girl is a literal teenager, most of them are either young, or socially awkward enough to come across that way.)

Sometimes the Monster Girl riffs on familiar monster forms, like Ginger, the girl whose adolescent changes include a transformation into a werewolf in Ginger Snaps; the vampires of Let the Right One In or A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night; or the title character in May, who has more than a touch of misguided Dr. Frankenstein. Sometimes they create their own hybrids, like Dawn, the pro-abstinence heroine of Teeth suffering from a case of vagina dentata, or the boy-eating demon who shares Jennifer’s Body. Sometimes there’s nothing explicitly supernatural about them — characters in The Neon Demon and the recent Titane probably qualify. What these sometimes disparate movies share is a sense that the characters’ experiences as young women in the world form their own horror shows.

The Monster Girl trope can sometimes play like an inversion of slasher cinema’s Final Girl: rather than facing down an external threat, the girl claims the destructive threat for herself, then struggles either with those instincts, or with another girl who hasn’t succumbed to her inner demons (like Needy in Jennifer’s Body, or Brigitte in Ginger Snaps). But the Monster Girl isn’t a direct spawn of the slasher movie — or the bad seed child-horror movie, which it also resembles. It has its own touchstones: The late ‘70s Brian De Palma thrillers Carrie and The Fury, for example, both feature young women with telekinetic powers. Carrie establishes the struggle between the sympathetic Monster Girl and the unchanged “nice” girl with what could be described as a brilliant hedge against its title character’s outcast status. Though much of the movie proceeds from the point of view of withdrawn, socially awkward Carrie White (Sissy Spacek), some scenes assume the POV of Sue Snell (Amy Irving), the “normal” girl who tries and fails to help Carrie. The Fury has even more points of view, plus espionage-like plotting, which makes it a more diffuse experience, less immediately keyed into the emotions of its young female lead (this time, Irving gets to play the woman who’s not to be trifled with). Still, it comes to a head with similarly bloody intensity.

Carrie ties its bloody climax to the rituals of girlhood, both physical (as Carrie is frightened and confused by her late-arriving period) and social (via the cruelty Carrie faces from her classmates, which sets off her powers early in the movie, and also enables her final vengeance at the end). The Monster Girl trope is almost always connected to these physical and/or mental changes in one way or the other: In Ginger Snaps, Ginger’s werewolf bite is brought on by a delayed period, while Teeth’s Dawn weaponizes her body (first accidentally, then with clear purpose) in tandem with her sexual awakening. It’s probably no accident that Snaps, Teeth, May, Let the Right One In, and Jennifer’s Body all came out during the 2000s, following the pop-culture domination of young female pop singers, who received mass attention for their looks and sexuality, while also being hounded by tabloids and scorned by men who assigned them the wispy shallowness of a sexual fantasy. (Plenty of horror fans would have been among those deriding the singers as pop tarts; in 2004’s Seed of Chucky, for example, an offscreen version of Britney Spears is murdered as a joke.) The Neon Demon, a little further removed from those days, is about pretty young things literally consumed with the desire to stay young, fresh, and desirable.

While these movies aren’t exactly girl-power revenge fantasies, many of them find a more organic way into the complicated ethics of “enjoying” a horror-movie kill. Not all of the Monster Girls’ victims deserve their sticky ends, and the counterpoint good girl is sometimes there to protest. Yet there is a satisfying kick to watching jerks, creeps, bullies, and rapists punished for their affronts, as they are in Teeth, or in the climax of Let the Right One In. Granted, it’s no less of a routine than the half-naked couple stalked by the masked man, and sometimes the repetition can be numbing. Teeth, for example, sly as it is, comes to rely on a pretty limited bag of tricks. But the Monster Girl has a way of simultaneously justifying and tempering the bloodlust of the modern horror movie: It’s fun to see some of the victims receive a comeuppance, while watching the Monster Girl lose herself in violence (Jennifer’s Body), loneliness (May), or both (Carrie) is still disturbing. And because the optics of pitting a male hero against a powerful woman can be so dodgy, these movies often create a space where multiple female characters control the narrative. Even when they’re ultimately pitted against each other, it tends to sting more than, say, the girl superhero fighting the designated henchwoman.

Maybe that’s why there are relatively few “boy” monsters in the Monster Girl mode. Horror has always included its share of sympathetic monsters who are portrayed as or coded male (the Universal Monsters sometimes inspire as much pity as fear), but they tend to have more outwardly creature-like appearances. The fish-man in The Shape of Water engages in romance (and more) with a human woman; by designing him to look more like the Creature from the Black Lagoon than an Aquaman-style undersea hunk, the movie trades one transgression (a human appearance masking monstrous abilities) for another (a monstrous appearance masking a human-like sensitivity). R, the zombie played by Nicholas Hoult in Warm Bodies, comes closer to a gender-flipped version of the Monster Girl trope, and his zombie nature has to be considerably softened — it’s revealed that he’s evolving back to a more human form — for the movie to hits its marks, which are more rom-com than horror, anyway.

Even when they delve into dark comedy or avoid traditional scares, Monster Girl movies are more decidedly horror, though they’re less dependent on creepy atmosphere. Familiar settings like old dark cabins, rustling in the woods, or creaky hallways of suburban homes might appear, but these stories don’t need to cut their characters off from society (and in many cases wouldn’t work in isolation from social dynamics). The characters’ particular hell also tends to be tied to their bodies, which are even more adept than boogeymen at following them everywhere.

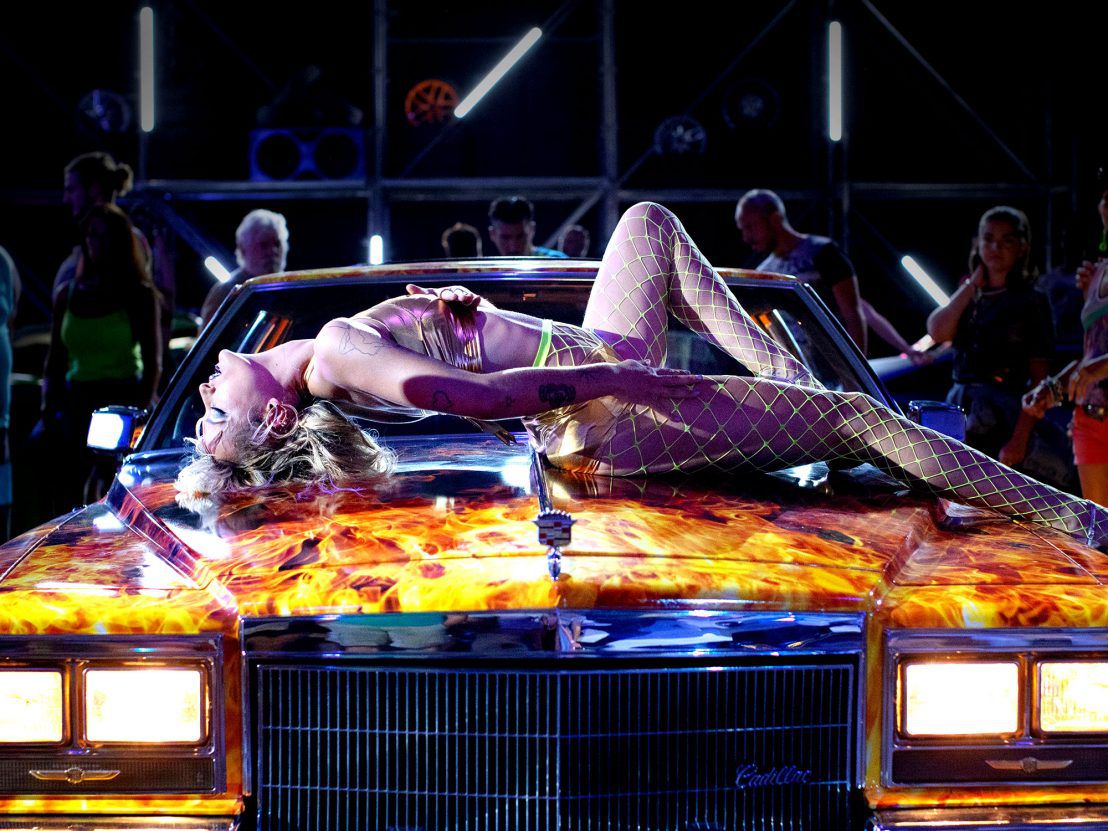

Titane makes this part of its story: Its antiheroine spends much of the movie on the run from her own life, where she’s committed multiple horrific, slasher-style murders between gigs as a semi-famous exotic dancer (of a sort). She bears a scar from a childhood accident, caused by the kind of unruly behavior that is both common in children, and apt to be referred to as monstrous by their parents. Throughout the movie, her body keeps changing, sometimes by her own design and sometimes by a body-horror plot device that is never fully explained; it’s an object of lust, fear, and transcendence, all at once. Titane and its many cousins understand that the Monster Girl trope can be liberating, as well as familiar, finding horror and beauty in a girl’s world with no shortage of either.

Source: https://www.polygon.com/22739140/monster-girl-horror-trope-carrie-titane

- All

- among

- APT

- Atmosphere

- audience

- Bears

- Beauty

- Black

- body

- car

- case

- cases

- caused

- Children

- claims

- closer

- Comedy

- Common

- confusion

- counterpoint

- Couple

- Design

- developed

- Early

- Elaborate

- emotions

- ends

- ethics

- experience

- Experiences

- faces

- facing

- Feature

- Figure

- films

- First

- form

- fresh

- fun

- good

- Growing

- head

- Home

- HTTPS

- human

- Humanity

- Hybrids

- Identity

- importantly

- isolation

- IT

- Kills

- lead

- Level

- Limited

- Loneliness

- man

- Men

- Modern

- movie

- Movies

- Neon

- optics

- Other

- parents

- physical

- play

- Plenty

- Plus

- Point of View

- protest

- proves

- Psychology

- Run

- seed

- sense

- Series

- Share

- Shares

- So

- Social

- Society

- Space

- start

- Status

- stay

- Stories

- superhero

- supernatural

- surprise

- The

- the world

- time

- touch

- trades

- traditional

- Transformation

- twist

- Universal

- View

- What

- WHO

- woman

- Women

- Work

- world

- worth

- year