When Nintendo announced that it would be shutting down the eShop for both the 3DS and Wii U in 2023, my reaction was simple: of course it is. The development wasn’t a huge surprise–after all, it wasn’t that long ago that PlayStation announced its decision to close down the digital storefronts for the PS3 and PS Vita (though this decision was ultimately reversed). Companies do as companies want, and mostly what they want is to make money, and to avoid wasting it. So of course Nintendo is closing down two of its older eShops. There’s no money in them. But for the rest of us, it sucks, right? My initial reaction was one of resignation, but after a conversation with my partner, my feelings quickly turned to frustration because of what we’re about to lose.

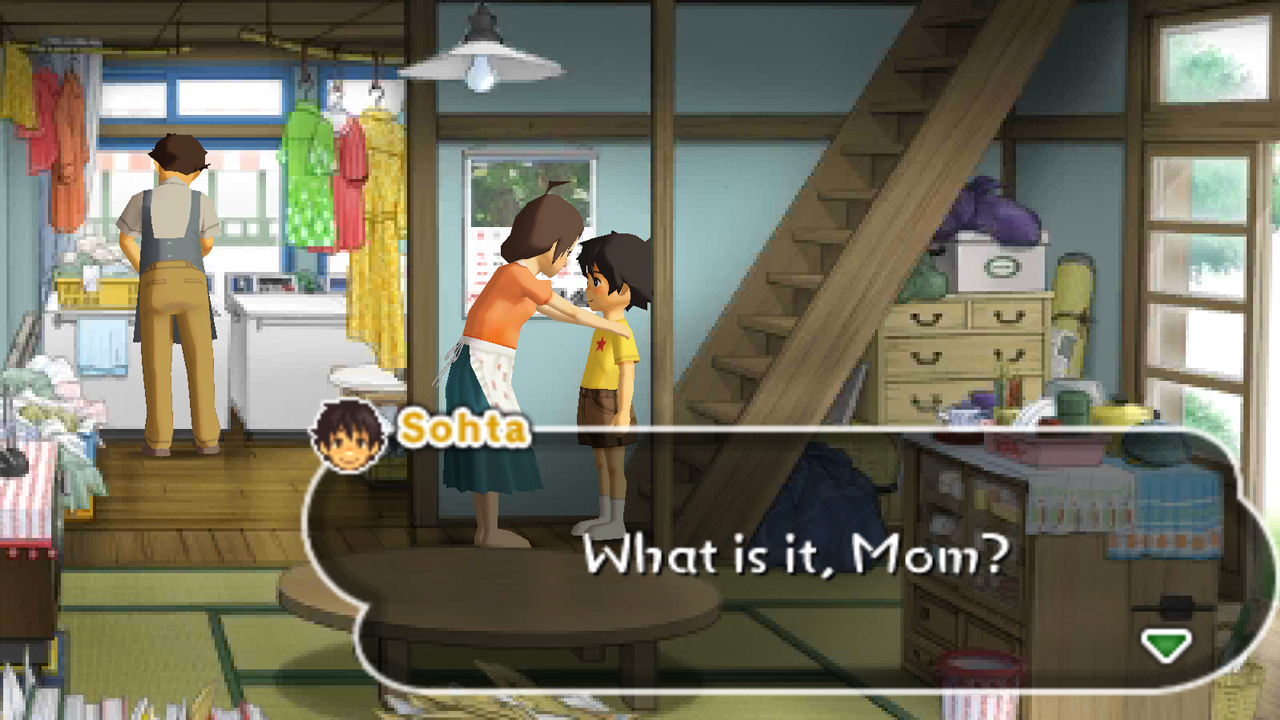

My partner is on a Fire Emblem kick at the minute. In fact, they only just got into the series properly after starting with Three Houses, and they’re now delving into the 3DS games. But after the eShop closes next year, Fire Emblem Fates: Revelation, the conclusive resolution to both Birthright and Conquest, will essentially be unplayable unless you’re willing to fork out hundreds of dollars on eBay for the very tough-to-find physical edition. Our combined irritation led me to think of all the other digital-only games on the eShop, like Attack of the Friday Monsters or Pushmo. Hell, even Pokemon Yellow won’t be legally playable again without owning a physical copy.

And so because of Nintendo’s decision, a number of games are going to be potentially lost in a legal capacity, just because that’s business. It’s clear the company isn’t interested in making those games easily accessible, either, as in the initial Q&A it released regarding the closure, Nintendo addressed players’ concerns by essentially saying it wasn’t obligated to make these games available. And unfortunately, that’s true.

Speaking with GameSpot, Iain Simons, writer and part-time curator at the UK’s National Video Game Museum, said, “In terms of fiscal responsibility to their shareholders, they likely don’t have a responsibility to make the titles available. So why should they? As their statement says, this is part of a ‘natural life-cycle’–all things must pass, games die.”

It isn’t just money that acts as a barrier, as Simons pointed out to me. Games are in a weird position when it comes to cultural recognition, and haven’t really managed to convince those who don’t play games that they are an art form worth spending time on. Mediums like film have the Oscars, an institution which–while far from perfect–still do better at presenting the format as art, opposed to something like The Game Awards, which is unfortunately more like an E3 press conference than an awards-focused show.

There are other complications when it comes to preserving games, too, such as the ways platforms are frequently changing; materials used to make games, like metal and plastic, are constantly degrading; and copyright issues. These all make understanding games from a cultural perspective incredibly difficult.

“From a preservation point of view, you dip your head into that for an hour and immediately realize that this is a huge problem that’s going to require vast resources and coordination to even begin to make it work,” said Simons.

There are people who are working to preserve as much video game history as they can, even if it is an immense amount of work, however. But in doing that work, there is also a huge amount of exasperation that comes with it. The Video Game History Foundation is one of the higher-profile organizations dedicated to preserving video game history. Its statement regarding the closure of the 3DS and Wii U eShops acknowledges the business side of things but criticizes Nintendo’s other actions.

“As a paying member of the Entertainment Software Association, Nintendo actively funds lobbying that prevents even libraries from being able to provide legal access to these games,” wrote the VGHF. “Not providing commercial access is understandable, but preventing institutional work to preserve these titles on top of that is actively destructive to video game history.”

What the VGHF is referring to is that the ESA (best known as the organizers of E3) has actively lobbied against games from being made available in public libraries. In 2017, Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE) of Oakland asked the US copyright office for a Digital Millennium Copyright Act exemption for preserving MMOs that their publishers no longer supported. Then in 2018, the ESA filed for MADE’s request to be denied, saying that “video game publishers have strong economic incentives to preserve their own games.” Thankfully, MADE was successful and the copyright exemption was granted, but only if the assets are legally passed on by the intellectual property owner. So if a company discontinues an MMO, it can choose to pass the game’s assets to preservationists. But even that limited ability to save defunct games might not be possible, especially when we can’t even guarantee the safety of the source code of video games.

The source code for the original Kingdom Hearts was infamously lost, so it’s a blessing that the game is even playable on modern consoles. And “blessing” is an understatement. Assets had to be recreated for the purpose of the remastered version of the game, and if Square Enix decided it wasn’t worth it, then the only legal way to play the game would be through the PS2 version.

However, according to Damian Rogers of the Game Preservation Society, it’s likely that at least some of the source code for games on the Nintendo eShop will have been saved. “We can also be fairly certain that, thanks to modern development practices and more foresight on the part of the developers, the games are safe internally as well, though we do wish Nintendo and all game publishers would be more transparent with the details of those internal preservation efforts,” Rogers said.

Transparency is one of the biggest issues at play here, certainly with a company like Nintendo. With the renewed interest in Fire Emblem, Nintendo might be working on some kind of port or remake of at least one of the series’ 3DS games, so perhaps they won’t be out of circulation indefinitely. But that doesn’t make up for all the other games that aren’t enjoying a sudden, unexpected resurgence and will be lost because of the eShop closure.

Sure, there are ROM sites, but Nintendo is constantly filing takedowns of these sites, with legal cases ultimately ordering the owners of them to pay millions of dollars. But these sites are doing more work to preserve older titles than Nintendo in many cases–just think of Mother 3, a game only playable in English thanks to a fan localization. But if a company like Nintendo has no interest in making its older titles available for purchase on its digital storefronts, or for preservationists and historians, there’s nothing anyone can legally do about it. And so we have a situation in which these games are unavailable both publicly and commercially. “But, ultimately, these [eShops] are commercial stores rather than public archives,” James Newman said.

Newman also does work for the UK’s National Video Game Museum, in addition to serving as a research professor at Bath Spa University. And like me, he is cognizant of how digital sales and streaming media can act as a deterrent from preservation. “One of the important shifts to be mindful of here is that the shift to digital distribution, subscription, and streaming brings with it a change in how we, as consumers, have access to our media. We no longer buy a film, album, or game in quite the same way, but rather we pay for access to it while it is part of the catalog and for as long as we continue to subscribe.

“This has a potentially huge impact in terms of our ability to watch, listen to, and play, and also on our ability to pass on our collections of media to future generations, whether that be handing them on through families and friends, or donating to museums and archives.”

That point of handing media on is something that struck a chord with me. Being able to easily share a game with someone just by giving them a copy is a special act. There’s something welcomingly communal about loaning your friend a DVD, and the idea of playing one of my favorite games with a kid of my own one day feels like an opportunity to pass on something a little bit more fun than my genetics.

There isn’t much that an individual can do to combat this. But Newman did provide an explanation of what people can help preservation efforts, even if it isn’t direct preservation work–which is to simply document these works’ existence. Documentation and recordings that provide an understanding of a game’s place in the cultural conversation are an important part of the process. “There is a tendency to think of game preservation as a software project to do with extracting data and emulating old or obsolete systems,” he said. “But game preservation is also a documentary project.

“Being able to play a game like Super Mario Maker in the future will be revealing and show how Nintendo gamified game-making and focused on placing and arranging tiles, but to really understand the complex meanings of that game, we would also want to see the levels that were designed by players and all those videos of people building them and reacting to them as they attempted to complete the sometimes fiendishly complicated and intricate puzzles people had designed.”

Newman is right–documenting games through things like walkthroughs, let’s plays, streams, all of it is important. But it also isn’t enough. While it might be more likely that companies are better at keeping their source code safe, there’s no guarantee that they actually are. And if Nintendo continues to be successful in shutting ROM sites down, it won’t just affect its own library of games, but games from other platforms hosted on the same site.

Nintendo is rightfully beloved as the company that makes so many wonderful games. But as with a number of other publishers, it’s also the justifiable target of ire the company that doesn’t want you to be aware of its rich history. When companies like Nintendo and organizations like the ESA are often the ones to have a major say in how games should be made available, we are put into a position where we can’t win. So for now the main thing we can potentially do is follow Newman’s advice by documenting these games, or at best, look into the ways we can help groups like the Video Game History Foundation. Because for as long as the bottom line doesn’t provide an incentive to do so, it’s clear that publishers aren’t going to do the work.

- Coinsmart. Europe’s Best Bitcoin and Crypto Exchange.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. FREE ACCESS.

- CryptoHawk. Altcoin Radar. Free Trial.

- Source: https://www.gamespot.com/articles/by-shutting-down-eshops-nintendo-again-stands-in-the-way-of-video-games-legacy/1100-6501634/?ftag=CAD-01-10abi2f

- "

- About

- access

- advice

- All

- announced

- Art

- Assets

- Association

- available

- before

- BEST

- Biggest

- Bit

- Bottom Line

- Building

- business

- buy

- Capacity

- cases

- change

- closure

- code

- cognizant

- Collections

- commercial

- Companies

- company

- Conference

- Consumers

- continue

- continues

- Conversation

- copyright

- data

- day

- dedicated

- developers

- Development

- DID

- digital

- direct

- distribution

- documentary

- dollars

- down

- e3

- eBay

- Economic

- emblem

- English

- Entertainment

- ESA

- eshop

- explanation

- families

- Film

- Fire

- focused

- follow

- fork

- form

- format

- Foundation

- Friday

- fun

- funds

- future

- game

- Games

- gamified

- Genetics

- Giving

- head

- here

- history

- How

- HTTPS

- huge

- Hundreds

- idea

- Impact

- important

- Institution

- Institutional

- intellectual

- intellectual property

- interest

- issues

- IT

- keeping

- large

- Led

- Legal

- levels

- Library

- Limited

- Line

- Lobbying

- Localization

- Long

- major

- MAKES

- Making

- materials

- Media

- metal

- Millions

- Modern

- money

- more

- mother

- Museum

- Museums

- National

- Nintendo

- oakland

- Opportunity

- organizations

- original

- Other

- owner

- owners

- partner

- Pay

- People

- perspective

- physical

- plastic

- Platforms

- play

- players

- Playing

- playstation

- Point of View

- Polygon

- possible

- press

- preventing

- Process

- project

- property

- public

- publishers

- purchase

- purpose

- Q&A

- RE

- reaction

- released

- research

- Resignation

- Resources

- responsibility

- REST

- s

- safe

- Safety

- Said

- sales

- Series

- serving

- Share

- shift

- Simple

- Sites

- So

- Software

- SPA

- Spending

- square

- Square Enix

- Statement

- stores

- streaming

- Streaming Media

- subscribe

- subscription

- successful

- Supported

- Systems

- Target

- The

- The Bottom Line

- The ESA

- The Source

- Through

- time

- top

- Uk

- university

- us

- version

- Video

- video games

- Videos

- View

- Watch

- What

- WHO

- win

- Work

- working

- works

- worth

- writer

- year