Horror trains us to confront loss. There is a thin line between tragedy and comedy, and horror walks upon that boundary by choosing from each and daring us to scream, cry, yelp, laugh, or otherwise let our emotions out. Don’t open that door! Don’t go down the stairs! Don’t wander out into the night! Don’t summon ghosts or demons! We collectively respond to horror because of the ebullience of that cathartic release, and because the genre has instructed us to know what’s coming within the confines of its format. And what’s coming is something or someone who will take from us, and force us to reckon with what’s left behind — and what’s left of us.

The us-vs.-them format is integral to nearly every horror villain: serial killers, zombies, ghosts, demons, monsters, things that go bump in the night. And for a long time, the elderly have been part of that “them,” too.

Elderly people have been used by a number of filmmakers as villains or jump scare providers: in Rosemary’s Baby, Mulholland Drive, The Visit, the Insidious franchise. And the elderly have their own agendas in many of these films: control and fear, typically. (Or even hunger, as in the 1988 Troma film Rabid Grannies, in which a pair of grandmothers eats its inheritance-greedy relatives. Understandable!)

Cynthia J. Miller and A. Bowdoin Van Riper write in the book Elder Horror: Essays on Film’s Frightening Images of Aging that the horror genre presents “a dark version of the familiar trope about the elderly: that their knowledge and experience extends into areas of which the young know nothing.” That analysis applies to many films that play with psychological, surreal, and even comedic horror. To Rosemary’s (Mia Farrow) neighbors in Rosemary’s Baby, who help in drugging her, raping her, brainwashing her, and forcing her to have a demonic baby. To the elderly travel companions Betty (Naomi Watts) befriends in Mulholland Drive, who reassure her that she has what it takes to make it in Los Angeles — and who then shrink down under her door, sneak into her apartment, and terrorize her at night. To the old spirits in the Insidious franchise, including the Bride in Black and Woman in White, who attempt to latch onto visitors in the Further and return to the physical world so they can live again. And to the escaped psychiatric patients in The Visit, who take advantage of the implied trust grandchildren place in their grandparents. (That film’s found-footage style “contributes significantly to the realism of the fear and uncertainty surrounding the grandparents’ aging process,” writes Stephanie M. Flint in her Elder Horror essay “The Limits of ‘Sundowning’: M. Night Shyamalan’s The Visit and the Horror of the Aging Body.”)

With that “old people are spooky” trope in place, in recent years a number of films have tweaked it by suggesting that the process of getting older is itself a kind of body horror. In Relic, Old, Bingo Hell, and The Manor, the fear of losing bodily autonomy through memory loss, illness, and decay is amped up to unsettling extremes. The recognizability of this transformation is key to our terror, and to the lingering disturbance with which these films leave us.

In Natalie Erika James’s Relic, Kay (Emily Mortimer) and her daughter Sam (Bella Heathcote) move in with their mother/grandmother Edna (Roby Nevin). The intergenerational relationships are fraught, and dread weighs as heavy as the black mold that has been growing in Edna’s home and on her body. As the black mold spreads, she becomes increasingly confused and violent: sleepwalking, wandering off, and accusing Sam of stealing. Is the house causing Edna’s increasingly damaged body, or is this the natural impact of her loneliness? Either way, Relic emphasizes that aging is irreversible, and that the breakdown of one’s body is a toxic process that spreads outward and affects our descendants.

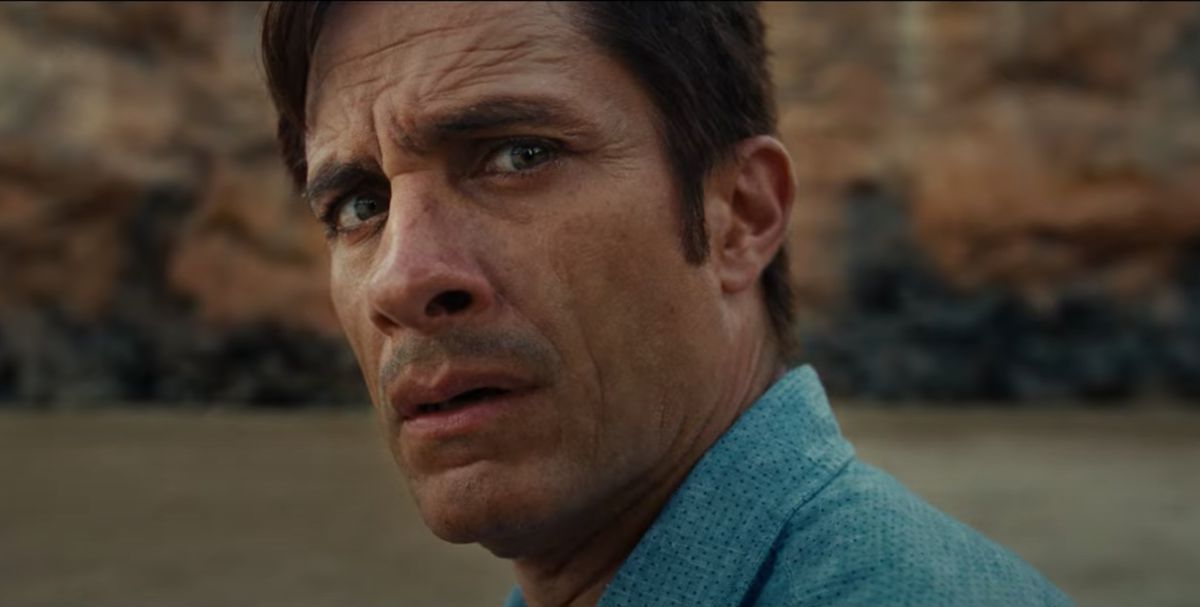

Old, an adaptation of the graphic novel Sandcastle by Pierre Oscar Levy and Frederik Peeters — and Shyamalan’s return to this trope after The Visit — makes a similar point about how aging affects not just the individual, but the people who they love and who love them. In the thriller, three groups spend a (literally) life-changing day together on a tropical beach. Without their knowledge, they’re visiting a place where they age a year for every 30 minutes they spend there, which means that whatever underlying medical conditions they have become grotesquely obvious. Everyone’s body in Old begins to betray them through schizophrenia, epilepsy, hypocalcemia, and haemophilia. But most tragic are the fates of the characters who come to the beach as young children and then rapidly age up to tweens and teens who have to face their mortality. Their jump from ages 6 to 11 to 15 turns them into figures their loved ones, relatives, and friends barely recognize, and with the passage of time comes the loss of opportunity. “There’s so many memories we didn’t have. It’s not fair,” says 15-year-old Kara (Eliza Scanlen), and given that Old came out during the COVID-19 pandemic, that line had widespread relatability.

Not to be left out, modern horror maestros Blumhouse Productions seized on this theme with two films through their Welcome to the Blumhouse partnership with Prime Video: Bingo Hell and The Manor. Both focus on the feeling of isolation that can come with the aging process: Will your family visit? Will they stay involved in your life? Or will they forget you?

Bingo Hell sets these musings in a neighborhood that is being rapidly gentrified, and where children and grandchildren don’t swing by as often as they should. Once the local bingo hall is bought by new owner Mr. Big (Richard Brake), the community’s elderly falls under the spell of his promised cash prizes — until longtime resident Lupita (Adriana Barraza) realizes that Mr. Big might not be as generous as he seems. The Manor explores a similar message about the desperation — and physical damage — brought on by the sense that one’s second chances are running out. After suffering a stroke, Judith Albright (Barbara Hershey) checks herself into a nursing home, to the shock of her beloved grandson Josh (Nicholas Alexander), who doesn’t see his grandmother as old. But once Judith is settled into the facility, she’s unnerved by how the staff doesn’t listen to the residents’ complaints about seeing strange things like a monster made out of tree bark and teenagers running around the grounds at night. The uphill battle Judith fights to be believed is a commentary on the disrespect with which we can treat our most vulnerable, and the frustration Hershey captures regarding Judith’s brain/body disconnect is a reminder that we’ll eventually feel this way, too.

These characters are all monstrous versions of “respect your elders,” but they also serve another purpose. Depending on your belief in the supernatural, it’s fairly rare to imagine waking up one day possessed or craving blood. But it is normal, and natural, and permanent, to wake up every day a little bit older. The elderly in horror will one day be us, and the aging process is the terror we cannot escape if we want to stay alive. And especially in the time of COVID-19, when staying safe means staying inside as much as possible. Our helplessness against the linear forward march of time is a horror of its own.

Relic is available through Showtime. Old is available for digital rental and purchase. Bingo Hell and The Manor are streaming on Prime Video.

Source: https://www.polygon.com/22745260/old-horror-movie-trope-rosemarys-baby-relic

- 11

- ADvantage

- All

- Amazon

- analysis

- around

- Baby

- Battle

- Bit

- Black

- blood

- body

- Cash

- chances

- Checks

- Children

- Comedy

- coming

- Commentary

- complaints

- COVID-19

- COVID-19 pandemic

- day

- digital

- Elderly

- emotions

- Epilepsy

- experience

- Face

- Facility

- fair

- family

- fights

- Film

- films

- Focus

- format

- Forward

- Franchise

- Growing

- Home

- House

- How

- HTTPS

- illness

- Impact

- Including

- involved

- isolation

- IT

- jump

- Key

- knowledge

- laugh

- Line

- local

- Loneliness

- Long

- Los Angeles

- love

- March

- medical

- MIA

- mirror

- Modern

- move

- Movies

- neighbors

- Nursing

- obvious.

- open

- Opportunity

- Oscar

- owner

- pandemic

- Partnership

- patients

- People

- physical

- play

- Prime Video

- Process

- purchase

- Relationships

- running

- safe

- seized

- sense

- sneak

- So

- spend

- stay

- streaming

- supernatural

- teenagers

- Teens

- The

- theme

- time

- trains

- Transformation

- travel

- treat

- Trust

- Universal

- us

- Video

- Vulnerable

- weighs

- What

- WHO

- within

- woman

- world

- year

- years

- Yelp