How to make a David: Engineering an upset

Before we begin, here are some details I’d like you to keep hold of:

- An LCK (Korean) or LPL (Chinese) team has won all but one Worlds where they’ve both attended.

- Since 1989 (32 years), only 3 small-market franchises have won the NBA Championship.

- An Iron Age sling could throw a stone with the force that a .45 magnum revolver shoots a bullet.

Keep track. Everything relates.

You are no Goliath but you could be a David

The bookmakers at Betway put NA’s odds of winning Worlds at 51-1. A one in 51 chance is just under 2% likelihood and according to one research unit, the real odds behind long shots are even steeper.

Look, you know the deal. NA is no Goliath. When it comes to PC esports, we’ve nearly always been underdogs. Examples like Liquid’s Grand Slam in Counter-Strike or Rapha’s absurd dominance Quake or Sentinels not dropping a game at Reykjavík—these are all exceptions to the rule that NA is the underdog in most PC games.

You probably know why, too. NA internet/ping issues. Low population servers. Competitive mentality. Lack of international competition. Best of ones. Coaching structure. Playstyle. Poor player development. Too many imports. Not enough imports. Chances are, you’ve heard it all before.

(Hell, I’ve even written about it before. I wrote the script for the video above, which gives a more detailed explanation of what’s going wrong for NA.)

What you haven’t heard enough about are the ways that the underdogs do win.

Every sport has specific examples of underdogs that not only pull off the upset but manage to become dynasties. True to the “David and Goliath” story, they reign after scoring the upset.

These underdog dynasties could serve as a guiding light for NA because the region’s issues are so structural that we’re not a Goliath but we could be a David. Strange as it may sound, the “David” that NA should look to isn’t in League or esports at all. It’s in small market basketball.

Small market basketball

In the NBA, we group teams by the size of their media market—a zone defined by the radio and TV stations you receive locally. These media markets basically outlined how big an audience a team had in terms of local broadcast. Given that basketball has long had lots and lots of games in a season, many of them you’d need to watch locally.

Big and small media markets quickly came to define the modern NBA’s power structure—big markets getting a distinct advantage because they could leverage broadcast, audience, and size into money and deals with shoe companies (read: more money). With money, you’d get star players and star rosters. Big in any sport, these stars are even more vital to basketball success. Once these big market teams begin winning, they create legacy, this legacy builds enduring fanbases, and before you know it a Los Angeles Lakers playoff game is as star-studded as the Met Gala.

For being a very different kind of game, League compares surprisingly well. It courts celebrity culture in a similar way (see TL+Asa Butterfield, 100T+Lil Nas X, DWG+Sunmi, K/DA, Seraphine). There’s an even more direct business link. aXiomatic, the ownership group behind Liquid, has a whole litany of basketball figures within it.

However, the most important link is the demographic one—the link between the size of the media market in the NBA and the size of the player base in NA. Where small market NBA teams struggle to attract and keep talent, smaller player base regions struggle to find and develop talent. The result is that NA has only ever gotten as far as the semifinals and no NBA team with a metropolitan area smaller than 2 million had won a championship—until the Milwaukee Bucks managed the miracle this year.

“I think it’s a pretty good comparison, right.” Jake “Spawn” Tiberi says. “You break it down, as far as smaller market that means you’re gonna have less chance of attracting superstar players. I think that’s very true for North America at the moment. […] I think it’s equally as hard to win Worlds as it is to win an NBA championship. Core and Damian Lillard probably are fighting the same fight out there,” Spawn chuckles.

One Knockout Punch

Spawn is Team Liquid’s Academy coach and director. He’s also an avid basketball fan and has his own unique experience with building up underdogs, first building ORDER (one of OCE’s strongest teams) and then building Team Liquid’s Academy team up out of a rough 2-year stretch.

Spawn is a key player in a wider movement within NA. This year, NA’s top orgs have focused more than ever on player development and on international talent from weaker, less-scouted regions (namely, OCE because they no longer cost an import slot).

Here too, the comparison between League and basketball holds. “It makes sense to how teams build in the NBA versus in NA as well,” Spawn notes. “As soon as you get a player like an FBI or a CoreJJ, they kind of become your cornerstone like a Damian Lillard would be in the Blazers and there’s a constant back-and-forth between trying to surround this person with enough talent to win, while still being this [small] media market team.”

(Pacers fans know well, it takes years of good turns to become an underdog contender – and one bad turn to go back to 8th seeds and first-round exits.)

Having been a Pacers fan my whole life, NA’s struggle has always felt painfully familiar. Your team does its best to bring in the single big name, then snowball that into increasing talent. For the small fry, it’s an option that you often have to take, given the raw talent gap that comes from the numbers.

And sometimes, the strategy works. The Toronto Raptors brought a top 5 player—Kawhi Leonard—in for one year and they made that year count. Alongside an insanely deep roster of solid players, Leonard and company got Toronto its first trophy. In the League world, Doublelift and CoreJJ did similar work against Invictus Gaming at MSI 2019.

Only, more often than not, this strategy doesn’t get you crown and kingdom—it gets you one good knockout punch. Even then, it takes luck for the punch to land.

Does Toronto win if the Golden State juggernaut doesn’t collapse from injuries and personality clashes? Does Team Liquid make MSI Finals if they draw into SKT or G2—teams that countered their style more than iG?

These are uncomfortable questions, but we should ask them. Especially if we want a roadmap to success that stays real, tangible.

The spur directs the horse

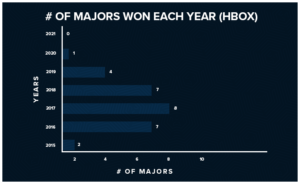

Basketball’s “David” comes from San Antonio. The San Antonio Spurs are one of the NBA’s most successful franchises, with five championships, six conference titles, and 22 division titles. They do it all while being comparable to NA in size: somewhere between small and middle market.

The Spurs’ five championships come during the peaks of Kobe, Shaq, and LeBron—goliaths of the sport. They’ve beaten them through modifying the normal small market model, supplementing it with strategies that apply on the court and in the team’s organization.

The Spurs do still incrementally build around stars (David Robinson, Tim Duncan), but they don’t play the hero ball that a lot of the NBA plays, where a team will feed their star the ball until they get on a hot streak and take over the game.

In contrast, the Spurs spread touches across the team. They layer screens, create pick and rolls, and open up so many passing lanes that they’re much more likely to get an uncontested shot. The Spurs make this strategy work by building deep rosters where most players are capable of 12-16 points in a game. That way, most open shooters make the shot and those shots become better than the contested ones a superstar would take.

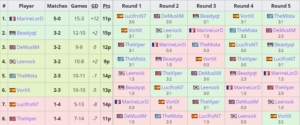

If this is a bit confusing, you could find a roughly even League example in Samsung’s 2017 Worlds run. The team had a strong star position in its bot lane duo (Ruler+CoreJJ) but they had the flexibility to operate in a few different ways and none of the team’s positions lead in laning stats at 2017 Worlds (save Ruler’s XP at 10 minutes).

When it came to the finals, the team’s mid laner, Crown, went from being the MVP that cinched the seta against a Longzhu superteam—to the dedicated Faker shock absorber. He played Malzahar and held Faker down for three games straight, clean sweeping the demon king off of a throne that he has since not been able to return to. For Samsung—a 3rd seed that fought through the regional gauntlet and play-ins—it was an inter-regional sort of underdog story.

The selfless system is one of the strongest, but it’s one of the most demanding. Every competitor wants to personally dismantle the enemy, to feed the ego. Take away that chance, and it can all fall apart.

After all, Kawhi Leonard forced his way out of the Spurs, while in League, Faker’s crown wasn’t the only one lost at the Worlds 2017 Finals. Samsung’s winning mid laner never returned to his peak either, seemingly haunted by the fact his biggest moment played out in three games of Malzahar.

This system’s construction and survival must come from patience and steady, smart development. Unlike many legendary NBA coaches, the Spurs’ Gregg Popovich did not so much wrangle stars into constellations as he polished diamonds in the rough.

Popovich pulled talent from surprising places, drafting from overlooked international leagues rather than popular US high schools and colleges. A feature from Seth Wickersham on ESPN details that this was to find team-oriented, ego-light players that were more familiar with a heavy passing style. It was also to find less contested players to sign to cheaper contracts—a kind of moneyball that San Antonio and most small markets need to play. For NA, that moneyball is no doubt appealing after being price-gouged into an 11 million dollar contract.

“I think that is a model that people are replicating right now,” Spawn says of the Spurs. “You have a look at it, FBI and Closer are 2 lesser-known players from minor regions that are at the top of their game right now. 100 Thieves is using that model.”

Though Team Liquid more tries to win over known stars, Spawn sees in our team the way that you create a gameplay formula.

“When you look at how CoreJJ played the game historically with Doubleleift, very bottom lane centric. When you look at how Alphari played the game historically, quite top lane focused, right? Being able to get in roleplayers like Santorin and Jensen actually shifting his game style a little bit to be a part of a big 3—[this] is kind of how these teams make it work in these markets.”

Spawn believes a big part of the success of the Spurs model comes from trying to hold onto a singular team identity as well as finding glue players. He uses Liquid’s jungler, Santorin as an example. Though he hopes Santorin will renew his contract with Liquid next year, he knows that it is expiring and anything can happen.

In that event, Spawn sees it best as finding another jungler that can be as team-oriented as Santorin. “In the theoretical world where he [Santorin] doesn’t [renew] but you have everyone else’s contract next year, you need to be able to plug a jungler in that does the same role as Santorin because you don’t wanna throw away 12 months of previous work by completely rebuilding a team when you’ve only replaced 20 percent.”

“I think that historically has been difficult to replicate in League of Legends,” Spawn admits, “because of a whole bunch of factors. Patches in the game every week, junglers have way different skillsets, it’s very rare to find someone as good as Santorin but also with the mindset of Santorin—that he’ll sacrifice so much for his lanes.”

TL has gotten flak for only playing one style, especially in the Doublelift era, but as the roster upgraded that style, they did crescendo into a 2019 MSI performance which might be the biggest upset in League history. Even with the struggles at Worlds, having that core style helped the team quickly elevate Tactical and then overperform in 2020—nearly escaping a group that felt very doomed.

Even doing all this, NA’s battle is still uphill and Liquid sits 1-2 in their group. Spawn adds that the Spurs themselves fell flat when they tried to keep their style by switching a retiring Duncan out for a similar player in LaMarcus Aldridge. Aldridge, while good, is no Duncan. NA, while good, is no China or Korea.

For many NA fans on the outside looking in, it’s all more reason for pessimism. The entire West collapsing on day 3 of Groups certainly cements the feeling. For some, even Cloud9’s miracle comeback from 0-3 will just seem a random, lucky break from the depressing norm. But from the inside, Spawn sees so many people pushing to make NA more competitive, to make those miracle runs, to make NA into a region that could be a David.

Building the Academy

Spawn obviously has a looming bias, being a coach in the Academy circuit, but look at the way top NA teams have interacted with the academy and amateur scene this year and you do see genuine, tangible improvements. The three teams at Worlds right now have embraced scrimming and working directly with their academy squad in a way that at least feels novel.

“When I took this job, I said to Jatt that this needs to be a squad,” Spawn said in an interview with Tim Sevenhuysen. “This can’t be your and my team and we get together every morning and we talk about how your team is going and how my team is going. When your team has a read on something, we need to have a similar read.

“It’s not like we’re only playing for the LCS team. When your bottom lane needs 2v2 practice, we’ll give it to them but when my bottom lane needs 2v2 practice, we expect that to be reciprocated. Same with top lane, same with mid lane, all the way down.”

Team Liquid stayed true to this course and from the academy split alone, reaped great rewards. In watching TLA play this year, there was always a ghost of the main squad there, especially with Eyla increasingly embracing a roaming, high map impact style, and Armao becoming even better at ganking and playing through lanes.

Then there’s the case of TLA top laner Jenkins, a player that many fans wanted Spawn to cut loose at the start of his tenure.

“Jenkins, at the start of the year, I remember when I re-signed him everyone was like,” Spawn slips into an weary fan-voice, “‘Oh my god, why are Team Liquid taking another chance on this guy that’s already been a part of their system for 2 years. Did Spawn not see that we came dead last, last year?’”

Fans had reason to criticize, given Jenkins had a mostly mediocre career in his 2 years of Academy—seeming every bit the veteran floater stuck in the second strings. In 2021, Jenkins shut the criticism down by leading the Summer Proving Ground top laners in KDA, landing 2nd in kill participation, and 3rd in gold and xp difference at 10. Even by the eye test, he looked revitalized.

The benefit for the LCS team became even clearer with Alphari’s brief benching. Jenkins subbed in and solo-killed CLG’s top laner, Finn and played solidly for the rest of his stay. Armao serves a similar case, subbing in for Santorin and facing off against an on-fire Blaber in Spring’s Grand Finals. Though Armao and Liquid ultimately got outpaced, a 3-2 series was much more than most expected.

While these academy promotions get marketed as a battle between players, Spawn recounts that Alphari and Core both wanted strong, direct ties with their academy counterparts. “Alphari was really big that he wanted the academy top laner to be a player that would be able to challenge him.”

“Jenkins would come in early and play 1 on 1’s versus Alphari and they would talk about the game. Yeon and Eyla played 2v2 versus Core and Tactical a lot. CoreJJ ran in-houses and Haeri played mid lane for CoreJJ.”

Spawn explains that, in a game with this many champions and matchups, the players need to learn how to cover niches and explore complexities through conversation with other top players. Hearing this was no surprise. When I interviewed Alphari a while back for Monster, he told me about his detailed research for top lane and how draining it could be. He acknowledged that it would be great to have staff cover this research—but it seemed unlikely. Jenkins at the very least makes the research easier.

When playoffs rolled around this summer, these academy teams became even more vital because the available scrim partners for top teams began to dwindle. The top teams with strong academy squads—TL, 100T, C9, and EG—all had a consistently powerful scrim partner. It’s no coincidence that 3 of the 4 went to Worlds and EG went to 5 games against 100T with a homegrown, rookie AD carry.

“Behind the scenes, we [TLA] were scrimming teams that were in the LCS and we had good results,” Spawn notes. It helped Liquid’s main roster that their most reliable scrim partner was near the strength of a handful of LCS teams—and Spawn’s coaching style may have made these scrims even more valuable.

Importing White Line Fever

Spawn is reputed to have a more strict and personal coaching style—something mirroring Popovich’s. When I ask him about it, he chuckles immediately but does give some specifics.

“My team never forfeits,” He says flatly. “My team generally always lets the opponent kill the nexus. There is a very small percentage of games where this isn’t useful […] but most of the time we will play the game from behind to a much higher extent than other teams.”

“The ability to deal with adversity is something that I really value. I’m super strict in that and if players start soft trolling, that’s when you have to have very serious conversations about why we do it. […] Throughout playoffs, we were down behind a lot against Cloud9 and 100 Thieves and we beat them both in best-of-5 [matches] coming from behind.”

(TLA mounts a comeback against 100T Academy down 7k, at their own nexus turrets.)

“I’m a stickler for being on time. I’m a punctual person and I expect punctuality. […] I’m really high on mastery, I’m really high on discipline, I’m really high on punctuality.”

This means when Team Liquid scrimmed TLA, they were getting little to no bullshit. In NA, and even in EU, it’s constantly rumored and whispered that teams don’t practice well, show up to scrims late, cancel early, soft troll against odd picks, and so on.

Alphari isn’t one to whisper. “The practice etiquette is disgusting,” the top laner said in a Liquid interview with Zane Bhansali published just earlier this week. Spawn keeps the “disgusting etiquette” out of Liquid and it’s part of what gave Liquid its best Academy results in years.

Spawn also borrows a great deal from traditional sports. He creates a real team hierarchy, with a captain that operates practically as an assistant coach—something seen in Australia’s rugby scene. He stresses that “Captain Armao” is more than a meme and players would regularly go to the most seasoned member on the roster for impartial input on lane.

“The other thing is—and it needs to be used sparingly cause people are people—every now and then you cop a spray,” Spawn says. It’s an Australian term for getting chewed out, yelled at. “You take your licks, is the way that I would say it.”

Spawn links a lot of these things back to Australian sports and the Australian culture around sports. It’s a culture worth replicating, especially considering Australia and New Zealand are very much the Davids of Cricket—a popular commonwealth sport. They rival or beat India, despite much smaller populations, due to what the Spawn and the Aussies call “White Line Fever.”

“Australians and New Zealanders are hella competitive people. In fact, I’ve never met a Kiwi or an Aussie that isn’t competitive. We get something called White Line Fever where we’re the nicest people in the world and then as soon as we cross the white line, we just turn into completely different people.”

(This short interview shows the relaxed affability of the Kiwi)

It’s immediately fitting for Spawn—who indulged 10 minutes of pure basketball questions with no relation to League in sight. It’s hard to imagine him angry, let alone laying into a player when it needs to be done. When I interview Haeri—TLA’s OCE mid laner—he is so laid back that I ask if that’s his dynamic in the team. Eyla tells me Haeri has the bigger temper between the two and Haeri admits it readily.

This is all part of what you import with OCE players. White Line Fever.

Not enough

What Spawn does, what C9 does with Max Waldo, what 100 Thieves has done with PapaSmithy, what EG does with Peter Dun and Kelsey Moser—this is all a big step in the right direction. It is still not enough.

If you watched the Groups Stage so far, you’ve seen some of NA’s best international performances to date. This is no joke. Despite what the record reads, all 3 NA teams have been ferocious in losses and have had their near misses in wins. Despite looking better, each team sits near the bottom of their group, looking at the same long odds of just making quarters, let alone winning. 4 LPL and LCK teams, Worlds is more brutal than it’s ever been.

(In TL’s game against Gen G, we see more fight than normal for NA. By attempting a play at Gen G’s outer tower, they at least force Gen G back to the middle-line of the map. This bit of tempo lets them push the top lane out again, which is partly what pressures Gen G into the bad dive that nearly turned the game.)

This is all to be expected. NA does not have the regional leagues of Europe, the solo queue of Korea, or the endless talent of the LPL. Making our system measure to theirs only makes it so we don’t slip behind the LMS. NA needs to do more if it’s to even be Toronto or Milwaukee—let alone the Spurs.

To do more, C9, 100T, EG, TSM, and TL will need to not only lobby Riot but appeal to League fans themselves. To move forward, NA will need to make decisions that may not be as profitable as Riot wants them to be or as entertaining as the average League fan wants them to be. But the Spurs didn’t win 5 titles by being interesting. They won it by passing the ball and having a superstar who was called “The Big Fundamental.”

The changes start with the structure of the competition itself. This year, the academy system quietly moved over to a best-of-2 system. Every set goes to 2 games, regardless of a team ties at 1-1. This system quietly carries a lot of benefit in League of Legends because it lets both teams play on both sides of the draft—red and blue.

Red and blue side carry different pick orders, one team getting the power of earlier picks and the other getting the power to have one final counter pick to help out a particular lane. NA has long struggled to work both sides of the draft and it’s in part because it’s harder to practice in a best-of-1. A best-of-2 not only lets both teams play both sides but it lets both teams innovate.

“Should we be lobbying hard for this?” I ask Spawn of the best-of-2.

“Yes please,” he says, exasperated. “I could just tell you having coached best-of-1’s, you are so much more pick safe, do anything for that one win in that one moment. […] In best-of-2, ugh,” Spawn sounds relieved just saying the words, “best-of-2 just allows me so much more freedom to like, you know, play Dhokla [TL’s 3rd string top laner] game 1.”

The argument against the best-of-2 (or best-of-3) is simply that it isn’t popular. All esports are a media industry and you do, ultimately, need to have viewers. In a region like NA, which simply does not care as much about PC esports as China or Korea, creating more games can create more trouble. Best-of-3’s bombed out in NA and best-of-2’s have an even weirder history.

(On the Bud Light Lounge, Spawn makes a compelling argument for how best-of-2s can increase the LCS’s entertainment value as well.)

Riot did try to run best-of-2’s in Europe but, in a major PR blunder, admitted that it was because Europe was more used to tie games than NA. True or not, this statement took literally all the focus and drew EU fans away from the fact that the format would almost certainly raise their region’s level over the long term. It would raise NA’s level too and it’s up to the League’s orgs and owners to aggressively market the new format as a level-up NA has long needed.

Fans will bemoan the 1-1 tie but they’ll also bemoan the static, stale style that NA regularly brings to Worlds. They’ll also bemoan the lack of creative drafting and poor counterpicking. This is where the best-of-2 becomes marketable. If a tie is boring, is it really any more boring than watching NA make a Groundhog Day of international competitions? Weird picks, fresh faces, stronger competition, a true regional identity, and hope for the future—this is how you sell the best-of-2.

It’s also important groundwork to lay for NA. Orgs need to get their fans accustomed to an important idea: Every game shouldn’t matter.

“Every game shouldn’t matter and that’s a good thing,” Spawn says. “If Team Liquid had been able to lock their spot on the ladder much earlier, you can start putting in players from Team Liquid Academy.”

“10,000 people-ish watch Academy. There are 100,000 people watching LCS and co-streamers are talking about it. Getting your players that you think are good enough to make LCS under that microscope is so valuable for an org.”

For their part, the savvy NA fans should begin demanding—and supporting—this too. Even the memers and shitposters have vested interest here because a successful NA means more chances to meme on EU. As we’ve seen all the way back in the halcyon days of imaqtpie, NA’s memers are at their best when clowning on their western brother.

(NA was forged in memery but getting serious will improve the memes too.)

While best-of-2’s are a great step forward, it’s still an equalizing measure since the LCK and LPL have been running best-ofs for years. To create a development advantage, LCS teams also need to pour resources into their development squads. The best way to do this starts with schedules and bootcamps.

This year, TLA’s Proving Grounds run got very weird as Jenkins and Armao were both called to Iceland as backups for the main roster. This left TLA’s main squad down 2 integral players during the biggest academy tournament of the year.

“They deserved the chance to prove that they could get Team Liquid Academy to a Proving Grounds Final in the same way that Eyla, Haeri, and Yeon deserved the chance of winning it all,” Spawn pauses. “But in saying that, I am not delusional. There is no way that playing two extra best-of-5’s in Proving Grounds has the same value of playing solo queue against Canyon for Armao.”

Spawn is correct but at the same time, this tradeoff did not have to exist—and if it doesn’t, it opens up some possibilities for NA. Namely, bringing the entire development roster abroad to play in a super server and to scrim internationally.

“Bootcamps are really useful, right? They’re expensive, they’re difficult to do sometimes, but there’s no debate that going somewhere else, experiencing different solo queue, different players, is inherently valuable to a region like North America. Oceania historically did it as well. We used to send all of our players to Korea in the off-season.”

Spawn notes that TL still could’ve chosen to send the entire TLA roster abroad, fielding an entirely different roster for the last bit of Proving Grounds. In the end, we chose not to, and given how close we came to winning Proving Grounds and how hard it is to coordinate travel these days, it made some sense we didn’t.

Looking forward, ideally travel becomes easier. Ideally, Proving Grounds doesn’t conflict with Worlds preparation. When those stars align, the top NA teams then need to spend the money and bring the entire Academy roster over to Worlds. We need this because we have to actively look for a way to develop talent beyond our own high-ping, low population borders. Doing any less means we may land a knockout punch here and there, we may knock down a Goliath or two, but the story will end there.

One good day, one good shot

Right now, Liquid’s story at Worlds isn’t over. This all may seem very long-term, very distant, but the here and now matters too. Only down a game, Liquid still has a chance to load the sling and create an upset. If they hit that shot and if NA begins its long-term push at the same time, you have the beginnings of a winning culture.

“All you need is for the stars to line up and for you to get the Tactical and the Jensen and the Alphari on your team and to build a really good culture. Then all of a sudden—and this is what sport is a lot of the time—you just need a day.”

For TL, the day approaches. “That day where we play 3 games in groups… We have a good day on that day, we get out of groups. And then that’s when belief starts happening.”

Of course, it’s difficult. Of course, the odds don’t favor us. But like a slinger in the bronze age, you only need that one shot—that one day. With the momentum of a proper swing, a bronze age sling could hit with the stopping power of a revolver. This is not to make a boyish celebration of a terrible thing like war but to give the lesson that so much comes with momentum.

“Teams with momentum—so scary,” Spawn picks up pace. “I’ll give you an example, every single best-of-5 we played in split 2 went to 5 games and we won every single one of them until Proving Grounds 2 when we were playing with Inori and Dhokla. My playing group just knew if we went to 5 games that we were gonna win.”

Even if TL, 100T, or C9 lose in quarters right after, escaping Groups alone provides momentum—and momentum makes strange things possible. Momentum begets belief, begets competitive culture, begets White Line Fever, OCE cricket, Spurs basketball, and maybe even a revitalized NA.

But even if we miss, even if we’re left depressed and pessimistic, we come home. We leave the sling and the war metaphors behind and we plant seeds, we plan, we build.

Writer // Austin “Plyff” Ryan

Graphics // Paula Valbuena