Darrington Press owes its position in the tabletop industry to the ubiquitous popularity of Dungeons & Dragons, the tabletop role-playing game equivalent to delivery pizza — inoffensive, widely available, and reliable in a pinch. Of late, the company behind actual play phenomenon Critical Role has tried to move beyond slinging cheap pies by releasing a tidy range of board games and, most recently, the cinematic-minded, magical-noir tabletop role-playing game Candela Obscura.

Its latest venture, Spenser Starke’s high fantasy RPG Daggerheart, walks back this exploration to offer a RPG that tastes very familiar to D&D with your eyes closed. Polygon grabbed an early look at Gen Con last week, spying the fresh ingredients and techniques Starke employs to construct a very simple pitch: D&D players deserve better pizza.

If you’ll allow me to stretch this metaphor a bit further, Daggerheart is not a calzone. While Starke and his team of designers have changed some of the composite parts — using a pair 12-sided dice instead of the conventional 20-sided die to resolve contests, for example — the result is still a fantasy melange setting where parties of adventurers undertake risks, fight foes, collect rewards, and level up. He told Polygon that 75% of Daggerheart’s design should feel familiar to players, a comforting crust to support palate-expanding flavors.

“I want to show people that there’s a whole world of games. So, through both Candela [Obscura] and Daggerheart, the goal from the beginning has been to say, ‘You can play any game that you want to, but I want you to know the options that you have,’” Starke said.

Cards and clarity

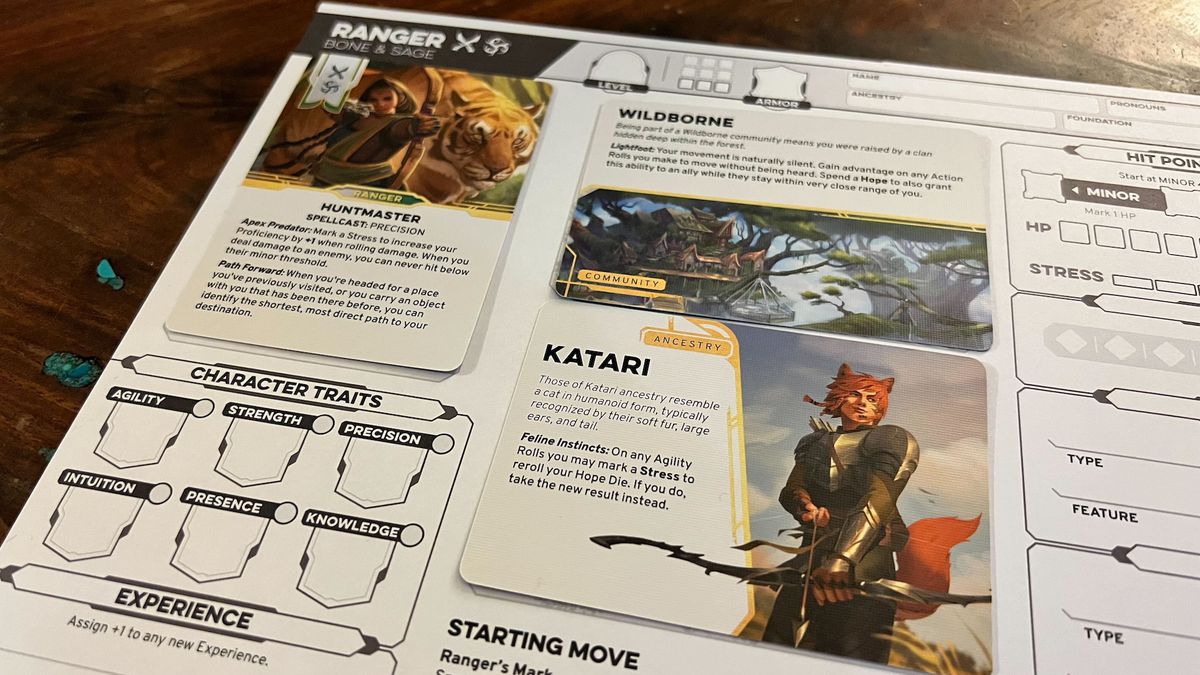

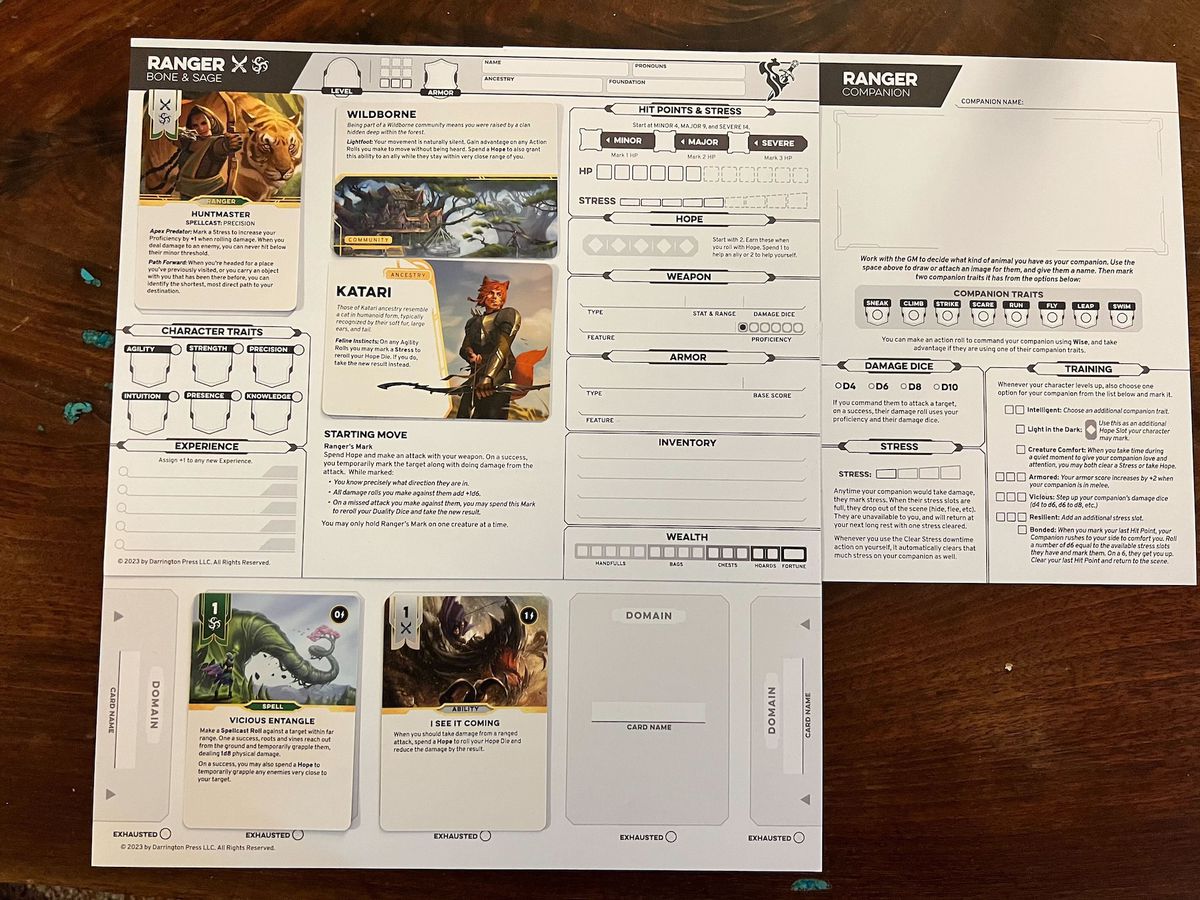

Laid out in the near-empty dining hall of an Indianapolis co-op, Starke excitedly shows off Daggerheart’s clever modular character sheet. It’s two pieces of paper, all told, and contains all the information one needs to play the game. During character creation, the back sheet is pulled out like an insert from a children’s activity book, revealing role-play prompts, reminders, and step-by-step instructions. Afterward, you slide it underneath, from left to right, where it then describes the process of leveling up.

True to form for the creator of Alice Is Missing, this sheet uses cards. Ancestry and community cards provide a character’s background — Daggerheart will have 27 of the former and nine of the latter upon release. He shows me the cards for a Wanderborn Clank, essentially a nomadic automaton, before explaining there’s also turtle and cat people. Classes use cards as well and are a combination of two domains from Daggerheart’s grand ring of overlapping ideals. For example, Rogues embody both Midnight and Grace, while a Bard combines Grace and Arcane in their performances.

If classes describe a character’s approach, their foundation card represents the application of that approach inside the fiction. A Syndicate Rogue may locate connections in any town they visit, empowering the player to inject their voice directly into the shared narrative. A Nightwalker, by contrast, gains access to stealth abilities they can use during combat, eschewing role-play strengths for tactical maneuverability.

Spell and ability cards are drawn from a class’s respective domain decks. The character sheet houses room for five cards at a time, while the rest go into their vault. These can be swapped around like readying spells during rest periods, though there’s always the option to pull a card from the vault at a variable cost in stress (more on that in a bit). All of this information fits neatly into rectangular gaps within the sheet’s layout, printed neatly alongside the array of six core stats — agility, strength, precision, intuition, presence, and knowledge — gear, connections, and other useful information. It’s tidy, thoughtful, and most importantly visible at a glance.

“My goal with this system is for players who are coming in to make characters to not even have to crack open the rulebook. If they don’t want to, they can sit down; they have all the cards in front of them. They want to flip through anything, they can just grab the cards that interest them, put them on a character sheet, and then play,” Starke said.

Hope for something new

As he explains the mechanics underpinning Daggerheart, two things become clear: First, Starke wears his influences on his sleeve, and this game likewise bears the legacy of John Harper’s Forged in the Dark system, the Powered by the Apocalypse design ethos derived from Apocalypse World, and even a smidge of Pelgrane Press’ 13th Age. Second, all that extra tabletop DNA can’t save it from clutching tight to a torch for the D&D audience.

Starke admits that Daggerheart is very much a power fantasy wherein you gain levels and unlock new ways to mete out violence, but that reduction ignores how the RPG’s many interlocking systems “encourage people to think about the narrative implications of the way that their character grows.” Stress can be spent to reroll dice but better serves to track how a scene influences characters beyond physical harm. Hit points aren’t exact numbers but broad ranges of minor, major, and severe, freeing both player and GM from the curse of crunching too much math during combat.

Hope might be the best example of how Starke is attempting to rethink RPG resource economies. This precious asset can be spent to aid others’ dice rolls at a one-to-one cost, or to help yourself for a small pump in price. When the hope die shows the bigger number — aka “rolling with hope” — players gain one tick in their hope pool. Upon being reduced to zero HP, a player can choose to lie unconscious but stable, rolling once to determine if they permanently lose one hope from their maximum pool. Starke mentioned a “fun little emergent design” where a character who kept dying found themselves with just enough hope to aid their friends but never enough to help themselves. Starke radiated excitement while wondering at the narrative possibilities.

The other “death moves” fulfill a similar player-empowerment purpose. Either you go out in a blaze of glory, performing one final act with a guaranteed critical success, or risk it all on a die roll between immediate resuscitation or instant, irrevocable death. Every action that led a player to that awful precipice should feel deliberate, weighty, and plugged directly into the shared story.

“I wanted to give people the experience that they sort of expect in a fantasy game, where it’s like, Yeah, I’m gonna level up; I’m gonna get some more cool stuff,” Starke said. “But also by embracing the level-up design approach of a more PbtA- or FitD-style game, it hopefully encourages people to think about the narrative implications of the way that their character is growing.”

Daggerheart’s chief selling point at present is the promise of reduced barriers to entry for new players that won’t sacrifice the interesting complexity that keeps veteran adventurers rolling. And while that’s a noble goal, the hour I spent peering at cards, character sheets, and a map full of minis told me nothing about the kinds of stories players will be empowered to create. Where are the GM tools used to craft mysteries, or the world-building tables for sewing together a brutal, resource-scarce hexcrawl?

One of D&D’s cardinal sins, something game design architect Jeremy Crawford has previously admitted, is an oversized focus on players at the expense of the one person tasked with building and portraying a world full of every possibility. It’s not clear whether Daggerheart, in its endeavor to build a bridge back to the D&D player base, will repeat the same mistake. Starke certainly views it as an opportunity to inform D&D players “there are so many other games out there” and that “they have the opportunity to play a game in the genre they want” without defaulting to Wizards’ bread and butter.

So, what is that genre? Walking away from the demo and contemplating the modular sheets, wonderful card-based character creation, and smart adoption of small-press RPGs’ best and brightest design trends, I’m left wondering if Daggerheart will be a shiny new machine that produces the same campaign-length, medieval-if-you-squint pastiche that D&D churns out at every table in the world. All these gourmet ingredients, kitchen utensils, and cooking skills, and we still might end up with just another pizza.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- ChartPrime. Elevate your Trading Game with ChartPrime. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.polygon.com/23831824/daggerheart-critical-role-rpg-preview

- 27

- a

- abilities

- ability

- About

- access

- act

- Action

- activity

- admitted

- Adoption

- afterward

- age

- aid

- Aka

- All

- allow

- alongside

- also

- always

- an

- and

- Another

- answer

- any

- Anything

- Application

- approach

- ARE

- around

- array

- as

- asset

- At

- audience

- available

- away

- back

- background

- barriers

- base

- BE

- Bears

- become

- been

- before

- beginning

- behind

- being

- belongs

- BEST

- Better

- between

- beyond

- bigger

- Bit

- board

- Board Games

- book

- both

- bottom

- Bread

- BRIDGE

- brightest

- broad

- build

- Building

- but

- by

- calls

- CAN

- card

- Cards

- Cat

- certainly

- changed

- character

- characters

- Cheap

- chief

- choose

- class

- classes

- clear

- closed

- collect

- combat

- combination

- coming

- community

- company

- complexity

- conditions

- Connections

- Construct

- contrast

- conventional

- cooking

- cool

- Core

- cost

- create

- creation

- creator

- critical

- curse

- Dark

- death

- delivery

- Demo

- derived

- Design

- designers

- determine

- DICE

- dining

- directly

- dna

- domain

- domains

- down

- drawn

- During

- Early

- economies

- either

- embracing

- empowering

- encourages

- end

- endeavor

- enough

- entry

- equivalent

- Essentially

- Ethos

- even

- Every

- Example

- excitement

- expect

- experience

- explaining

- explains

- exploration

- eyes

- familiar

- FANTASY

- feel

- Fiction

- field

- fight

- Final

- First

- Fits

- Focus

- For

- forged

- form

- Former

- Foundation

- fresh

- Friends

- from

- front

- Fulfill

- full

- further

- gain

- gains

- game

- Games

- Gaming

- gaps

- Gear

- Genre

- Get

- give

- glance

- GM

- go

- goal

- grab

- grace

- Growing

- grows

- guaranteed

- Hall

- harm

- has

- Have

- he

- help

- High

- his

- HIT

- hope

- Hopefully

- hour

- houses

- How

- HP

- HTTPS

- i

- if

- IMMEDIATE

- implications

- importantly

- in

- industry

- inform

- information

- inject

- INSIDE

- instant

- instead

- instructions

- interest

- interesting

- into

- intuition

- Is

- IT

- ITS

- john

- jpg

- just

- kept

- know

- knowledge

- last

- late

- latest

- layout

- Led

- left

- legacy

- Level

- level up

- levels

- lie

- like

- Little

- Look

- lose

- machine

- major

- make

- many

- map

- math

- maximum

- May

- me

- Mechanics

- might

- minor

- modular

- more

- most

- move

- much

- narrative

- needs

- never

- New

- Nine

- not

- notes

- nothing

- number

- numbers

- of

- off

- offer

- on

- once

- One

- One-to-one

- open

- Opportunity

- Option

- Options

- or

- Other

- out

- pair

- Paper

- parties

- parts

- People

- Performances

- performing

- periods

- permanently

- phenomenon

- physical

- pieces

- pitch

- Pizza

- plato

- plato data intelligence

- platodata

- platogaming

- play

- player

- players

- Plugged

- Point

- Points

- Polygon

- pool

- popularity

- position

- possibilities

- possibility

- power

- powered

- precious

- precipice

- precision

- presence

- present

- previously

- price

- Process

- produces

- promise

- Provide

- pump

- purpose

- put

- range

- Readying

- recently

- Reduced

- reduction

- release

- releasing

- reliable

- Repeat

- represents

- Resolve

- resource

- respective

- REST

- result

- revealing

- Rewards

- right

- Ring

- Risk

- risks

- Rogue

- role

- Role-Playing

- Roll

- Rolling

- rolls

- room

- RPG

- Said

- same

- save

- say

- scene

- second

- selling

- serves

- setting

- severe

- shared

- sheet

- should

- show

- shows

- side

- similar

- Simple

- Sit

- SIX

- skills

- small

- smart

- So

- some

- something

- spying

- stable

- stats

- Stealth

- still

- Stories

- Story

- strength

- strengths

- stress

- success

- support

- syndicate

- system

- Systems

- table

- Tabletop

- tactical

- Team

- techniques

- that

- The

- The Game

- The Vault

- the world

- their

- Them

- themselves

- then

- These

- they

- things

- think

- this

- though

- Through

- time

- to

- together

- too

- tools

- torch

- track

- Trends

- tried

- two

- ubiquitous

- underpinning

- unlock

- up

- upon

- use

- used

- useful information

- uses

- using

- Vault

- venture

- very

- veteran

- views

- Visit

- Voice

- walking

- want

- wanted

- way

- ways

- we

- week

- well

- What

- What is

- when

- where

- whether

- while

- WHO

- whole

- widely

- will

- Wing

- with

- within

- without

- wondering

- world

- you

- your

- yourself

- zephyrnet

- zero