I recently got around to reading Hideo Kojima's The Creative Gene, a collection of essays by the designer on a diverse range of pop culture topics: re-issues of animes he liked watching as a kid, reviews of new science fiction novels, retrospectives on great movies. As anyone with an interest in Kojima's work might expect, it is a book that veers between searing insight and tiresome navel-gazing. You're absorbed on some pages, and your eye's flicking to the next paragraph on others.

While the book is a grab-bag of essays with no real through-line, it does have a theme—loneliness. When Kojima writes about a given topic, his tendency is to connect it to periods in his life, some of which are described in great detail. The book is full of ghosts, Kojima's father in particular, and how Kojima thinks about certain works is bound-up with his first experiences of it in the context of his own life. While the overall tone of things always returns to the triumphal—Kojima never shies from adding in a reference to his own hugely successful ouvre—it is a book shot-through with feelings of isolation and, in some cases, futile regret.

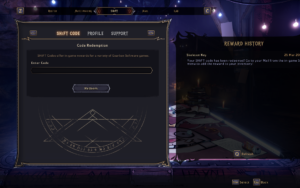

This was a good staging ground from which to embark once more on Death Stranding's journey across a near-future and wasted landscape. Death Stranding: The Director's Cut adds a whole bunch of new stuff to the game (read about it here), though this all seems mostly backloaded and the first 12 hours or so are familiar from my first playthrough at launch.

Except… the world's a bit different. Death Stranding was released in November 2019. A month later, a novel virus outbreak was detected in Wuhan, China, and within months almost the entire world had entered some form of coronavirus-related lockdown.

“The world was designed such that Sam almost never sees another human being in the flesh.”

Let's not overdo things here but, like everyone else, I've gone through two-and-a-half years that have been spent mostly at home, the first year almost entirely. I now live in a world where I don't even notice the plastic screens at supermarket checkouts anymore, nevermind find anything unusual about passing dozens of masked individuals on a town walk, and where my kids sometimes come home from school and I have to jam a cotton bud up their nose.

Everyone has gone through some version of this. And so the things that Kojima was noticing about our society, and making core to Death Stranding, have become acutely magnified through this lens. The most obvious point to make is that you play a deliveryman, and we've just gone through a spell where delivery people could be the week's only face-to-face human contact: as Larkin wrote in Aubade, “postmen, like doctors, go from house-to-house.”

Parts of Death Stranding now land differently. The world was designed such that Sam almost never sees another human being in the flesh outside of cutscenes: the vast majority of deliveries are made to functional industrial-style bunkers, where you're thanked by a hologram projection and sent on your way with new deliveries. There's the CODEC calls but Sam is nearly always—with the exception of BB, which we'll come to—alone in a vast landscape.

Thanks to having played it through already, I'm much better at Death Stranding now: one of its nicer elements is that this isn't really a game where the difficulty is skill-based, but more about thinking. I approach deliveries with patience, planning, the right gear, and a bit of knowledge. I plan routes now (I know, I know, I should've been doing this first time).

And while I'm walking slowly along, back loaded up like a forklift truck, I've been thinking about the interactions Kojima Productions put in. I'd initially forgotten that Sam could shout out to the hills, until a mis-placed 'like' activated it: now, just like when I'm on a walk myself, I every-so-often talk to myself.

“

Thematically at least, Death Stranding is at its weakest when it later adds more traditional elements.”

This world is, to begin with, almost all nature. The human structures that exist are disparate, brutalist blots on the landscape, nibbled-away at their edges by flora. You begin the long trek up a mountain knowing with certainty you won't bump into anyone else on the way. Half the time you forget that BB's even there: until you start fooling around with the 'soothe' interactions, and now I feel guilty if I see a spectacular view and don't treat BB to some photo mode.

I suppose you could describe Death Stranding's arc as Sam, the outcast, becoming the common strand that ultimately binds various groups together. But the game's power doesn't come from that rather pat conclusion. It comes from the fact that Sam is this lonely outsider figure for the most important parts of your experience. Thematically at least, Death Stranding is at its weakest when it later adds more traditional elements, such as shooting sections and more regular 'combat' encounters, because its strongest theme is loneliness.

Kojima made a game that is about how the lifestyle in developed societies is driving us into isolated groups, and how this leads to a collective inability to act on an existential threat like global warming. What happened in the real world with the pandemic, however, seems to me to have made Death Stranding's underlying atmosphere of loneliness the most prominent part of the experience.

A funny thing happened the other day. I live in a semi-rural place, and have to walk up a muddy hill to the nearest stores. I carry it all in a backpack and, as I was coming back down, readjusted the weight on my straps. Just for an instant I felt like Sam, and smiled at the thought of it, returning to home base with the deliveries in S-rank condition.

It made me think of something else, too. In Kojima's book The Creative Gene, he has an essay about Taxi Driver where he writes about how he identified with Travis Bickle: to the extent he started dressing like him.

“But what moved me to tears was not the story, the direction, or the actors' techniques. It was because, through experiencing Travis's loneliness secondhand, I learned that other people, somewhere out there in the world, were like me.

“I'm not the only one who thinks he's alone! A man with the same kind of feelings of isolation as me is out there driving a taxi. The thought alleviated my loneliness.

“After the movie was over, I bought the same military jacket as De Niro wore for his performance, put on leather boots, and went out into the city. To complete the imitation, I thrust my hands into my pockets and walked with a slouch. As I walked the streets as Travis, something seemed to have changed. It wasn't that the movie had taught me how to battle my loneliness; Travis taught me how to keep its company.”

That moment of imaginative empathy, large or small, seems like a great thing for a game to leave behind. While I'm a fan of Kojima's work, one has to accept that his games do bludgeon you over the head with 'narrative meaning' at times: but what sticks with me most in Death Stranding is a feeling. It hits even more profoundly years after launch than it did at the time: that moment of loneliness in the world, and whatever it is we doggedly walk towards.

- "

- 2019

- About

- across

- All

- Another

- approach

- around

- Atmosphere

- Battle

- Bit

- Boots

- Bunch

- cases

- China

- City

- collection

- coming

- Common

- company

- Conclusion

- contact

- could

- Creative

- credit

- Culture

- day

- Death Stranding

- Deliveries

- delivery

- designer

- detail

- developed

- DID

- different

- Director

- Doctors

- down

- dozens

- driver

- driving

- embark

- Empathy

- experience

- Experiences

- Fiction

- Figure

- First

- first time

- forgotten

- form

- full

- funny

- game

- Games

- Gear

- Global

- good

- great

- having

- head

- here

- Hills

- Home

- How

- How To

- HTTPS

- human

- i

- image

- important

- in death

- interest

- isolation

- IT

- journey

- kids

- knowledge

- large

- launch

- learned

- lifestyle

- lockdown

- Loneliness

- Long

- Majority

- Making

- man

- Military

- months

- more

- movie

- Movies

- Nose

- Other

- outbreak

- pandemic

- People

- performance

- planning

- plastic

- play

- Point

- power

- Projection

- range

- RE

- Reading

- real world

- released

- returns

- Reviews

- s

- School

- Science

- science fiction

- sees

- small

- So

- Society

- start

- started

- stores

- Story

- successful

- techniques

- The

- the world

- theme

- Thinking

- Through

- time

- together

- Topics

- towards

- traditional

- treat

- truck

- unusual

- us

- version

- View

- virus

- walking

- What

- WHO

- within

- Work

- works

- world

- year

- years