It’s August 16th, 2008. The 11th Touhou game, Subterranean Animism, releases today at Comiket, trying to buy a copy is an intense one. People queue in the hot sun for hours before being crammed into the Tokyo exhibition hall’s cacophony of stalls. Hundreds of thousands of people will flock here over the next few days, every one of them hot, bothered, and thoroughly dehydrated. Finding Touhou creator ZUN’s table amongst this flood before his stock runs out is a feat in itself, but it’s worth the sweat and exhaustion for the reward: a freshly pressed CD containing a great shmup that. Braving the crowd and heat in person is the only sure way to get one.

Doujin games are the ‘Why not?’ response to the wider gaming industry’s ‘Why?’

XSEED executive VP Kenji Hosoi

It’s now 2022. Today, you, sat in your comfy desk chair—or perhaps curled up on the sofa with your Steam Deck—bought and downloaded Subterranean Animism in under a minute after casually browsing the hundreds of other doujin games available on Valve’s store and then carried on with your day. For anyone who followed Japan’s doujin game scene in the early 2000s, it’s still surreal to see some of the most underground games built for tiny, insular communities now a button click away on Steam.

Long before the indie game boom of the last decade, Japan’s doujin games served as its own sort of indie scene. “There are many opinions on the definition of doujin, but I believe… 同人(doujin) means individuals or groups who share the same interests and preferences,” says Piro, representative director of small Japanese publisher Henteko Doujin. “While ‘indie games’ are classified by the scale of production as works that do not belong to a major label, ‘doujin games’ are classified by the purpose of production as works for people with the same tastes.”

Or to put it another way: Doujin games aren’t a genre, they’re an attitude.

But has that attitude changed now that doujin games have gone from being homemade media physically handed over to fellow fans to something available worldwide to virtually anyone at the click of a mouse?

By fans, for fans

Sometimes manually burned at home onto unbranded CD-Rs, sometimes professionally pressed onto DVDs with slick colour labels, doujin games have always been charmingly unpredictable. They may be wholly original works—ZUN’s ever-expanding series of Touhou shmups and the aquatic warfare of Ace of Seafood—or they may be fan games that, ahem, “borrow” existing intellectual property. A perfect example is Densha de D, which combines Taito’s train simulator Densha de Go! with the famous manga Initial D, letting you drift race trains through Tokyo at 160 km/h.

XSEED Games’ executive vice president Kenji Hosoi describes doujin games as the “Why not?” response to the wider gaming industry’s “Why?”, explaining that for these maverick developers the usual rules need not apply. “The reason can be ‘just because,’ which I think is what makes some of these developers come up with fascinating ideas,” Hosoi says. “When you’re not thinking about game development based off of specific audience buckets and user trends, the entire world becomes your potential audience.”

Doujin’s positive can-do approach has led to games like Fight Crab, an arena fighter where crustaceans with swords and guns duel to the death, and the playable nightmare that is Corpse Party and its strangely appealing combination of bloodsoaked halls and cute pixel schoolkids. The only constant in doujin gaming is the lack of consistency.

For a long time this all-you-can-eat buffet of creativity was virtually impossible to play outside Japan without either:

- Paying inflated sums to retailers so small their websites were simply text-only descriptions and an email address

- Following links of dubious legality on a specialist forum and praying the eventual result wasn’t riddled with malware

That all changed in 2010, when Recettear: An Item Shop’s Tale made its Steam debut.

Carpe Fulgur’s trailblazing localisation of the shop-running game couldn’t have been a more perfect introduction to doujin games. Recettear was like nothing else at the time with a little bit of action, a lot of heart, and a localisation keen on sounding warm and natural to English-speaking players—a world away from the fierce and often untranslated shmups that were traditionally the doujin gamer’s genre of choice.

But as vital as all that was, it was the delivery method that made doujin gaming explode.

I don’t think too much about sales, but rather prioritize releasing games that are new to the world

Henteko Doujin director Piro

Japanese PC games of all genres and sizes had been released in English before: even Recettear’s developer had one of its earlier games published on disc in no less than five languages. The only problem was these launches were so small it often took blind luck just to learn they existed, and buying them, especially in the small window of new that helped publishers fund further daring releases, was virtually impossible.

Steam not only did away with needing to scour eBay and obscure forums for doujin games, but the uniform appearance of its store pages also made Recettear—and by extension doujin gaming as a whole—the best kind of ordinary. For the first time ever this import-only niche of a niche was affordable and available to a wide audience, requiring no second-hand reports from doujin extravaganza Comikets and no greater effort to buy than the click of a mouse. And the store was infinitely more secure than emailing credit card details to an unknown person and hoping for the best.

Carpe Fulgur’s pioneering effort had a snowball effect on the entire industry, and today Steam has hundreds of doujin games to choose from, encompassing everything from dense ‘sound novel’ series Higurashi When They Cry to the non-stop bullet-dodging action of Crimzon Clover, to Touhou Genso Wanderer’s colourful take on dungeon crawling. It’s a happy situation that’s only made the process of getting doujin games on Steam easier for everyone involved.

“It does help having published titles like Sakuna and Corpse Party when speaking to doujin/indie devs,” says XSEED’s Kenji Hosoi. “Thanks to the high quality of these titles, it conveys a certain level of trust in our pedigree as a publisher.”

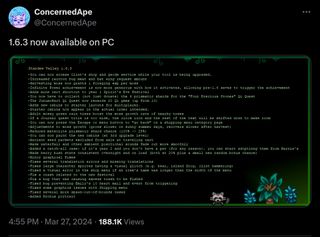

There’s no sign the doujin scene will do anything other than continue to flourish on Valve’s store. The recently released Gradius-like shmup Drainus currently has a “Very Positive” rating after receiving hundreds of user recommendations, Touhou-themed Castlevania-like Koumajou Remilia: Scarlet Symphony is receiving a cross-platform multilingual release after appearing to be lost down the doujin cracks forever, and every doujin-friendly publisher’s “Upcoming” page has multiple games just waiting to be wishlisted.

These games have gone from being rare novelties to completely integrated into Steam’s ecosystem in the space of a decade, to the point where XSEED no longer makes the doujin distinction when it releases new games. Why wouldn’t a doujin game do well on Steam? Why couldn’t something as unusual as Sakuna: Of Rice and Ruin sell amongst the constant stream of big-name hits from infinitely larger studios?

“At the end of the day, the most important thing is the quality of the game and how the game is accepted by the fans,” says Hosoi. “Sakuna was one of those rare titles that everyone on our team enjoyed playing. It was unanimous that we all liked the characters, artwork, gameplay, story and it was just a no-brainer for us, even if ‘rice making’ was a niche concept to market.”

Commercial and critical success is found in every genre and at every price point for doujin games, as Piro points out. “In most cases, doujin game developers are very pleased with the response from new markets and enthusiastic audiences.” Newfound international acceptance has only reinforced the creative side of the scene, the sheer size of Steam’s user base giving doujin publishers with doujin mindsets the space to thrive.

Comiket, the event you once had to attend to find rare doujin games, circa 2008

“Our policy is to work in the spirit of doujin, even as a publisher. I don’t think too much about sales, but rather prioritize releasing games that are new to the world and that even a small number of people enjoy enthusiastically. Even so, we have achieved good results in terms of sales too,” explains Piro.

It’s a system that seems to work for everyone involved—for now. Is there a danger this bigger audience will change the spirit of doujin, that the desire for international acceptance will see the emergence of safer games with a less distinctive personality for sales’ sake? Hosoi doesn’t think so.

“I don’t think the core concept has changed as it’s always about making things you like,” he says. “There may be new ideas coming out of the culture, but that’s also always been part of what defines it… I think it’s going to be stronger than ever, with more possibilities, and an ever-growing audience.”