Rise of a Nazgul

“My matches!?” Victor “Nazgul” Goossens asks, shocked when I tell him that I’ve been watching some of his old StarCraft: Brood War games.

It seems like it shouldn’t be surprising because according to his own words, he was one of the best players in Europe and maybe the world for parts of 2002 and 2003. “In Brood War, there’s like a good 1 or 2 years where I am—in my opinion—arguably the best player outside of Korea.”

Nazgul notes this without boasting. As with most of the praise Nazgul gives himself, he’s even quick to add some caveats. “Does not mean the best Western player. I think you could argue when Elky [a legendary top French player] lived in Korea he was better [than] when I didn’t live in Korea, for example.”

The caveats aren’t there to bring himself down as much to keep the record straight. This is because, after about two full decades, the record is hard to keep at all—let alone keep straight. Nazgul has good reason to be surprised because In the beginning when Brood War was molding itself into the esport to be, many of the recording methods we now take for granted were still in the making and many of Brood War’s oldest matches never made it to the archive. (Plus, the matches that did survive tended to come from Korea, not from the West.)

“I still remember when replays came out,” he recounts. “You have no VOD, you have no stream, you have no replays. The only way you could ever see another person play StarCraft was literally join their game as an observer and watch. It was the only way! Then replays came out and it was mind blowing.”

“Different time,” says Nazgul.

Different time [2000-2002]

To put the time in full context, replays came out on patch 1.08, on May 20th, 2001—a full three years after the game’s release on March 31st 1998. StarCraft had a pretty large audience but like traditional sports, the matches needed to be recorded the old fashioned way. In South Korea, StarCraft basically was a traditional sport, being televised and broadcast to young audiences there.

The issue was, beyond those top Korean competitors and the region as a whole, the recording process was less like a traditional sport and more akin to early fighting games, arcade scenes. You may find some big moments here and there but many details and videos are lost to time.

Nowadays, finding pre-2004 Brood War matches outside of Korean leagues range from tough to impossible, even for players at the top, like Nazgul.

(This replay cast of 5 ladder matches between Nazgul and Boxer is one of the best remaining Nazgul VODS out there. With casting from TL.net regular/writer BisuDagger, it’s also one of the only ones with English commentary.)

In some ways, this makes sense because Korea was simply so far ahead of the rest of the world. It’s something you can read straight from the language of the game. If you were from anywhere but Korea, you were just foreign. The international players that could actually compete with Korean professionals were so few and far between that you could lump them into one category. Foreign scenes being so behind, they weren’t nearly as likely to be recorded, documented, and saved for literally two decades later.

When Nazgul was coming up in the early 2000’s, there was basically no video sharing either. So the West isn’t even seeing the top level of Brood War, happening right then on Korean television.

Enter TL.net.

“When the website opened up, stream doesn’t exist, VOD does not exist, right? So there’s these professionals playing on Korean television and the West has absolutely no way of following StarCraft as a professional sport,” Nazgul says.

“So we had predominantly Korean American writers who at that point in their life lived in Korea, watching matches on TV just writing down battle reports on what was happening. Then their writing was published on TL.net and that was basically the core of how it all started and people loved reading up on it and what was going on.”

“If you told someone now, they’d be like, ‘wait, I can’t sit still and read that long.’ But back then it wasn’t even a consideration. If you literally don’t have the other things, and it’s the only thing, there’s just so much appreciation for it. […] We basically grew up with written word being the core of Team Liquid.”

It feels bizarre to imagine given how visual esports has become. But battle reports were vital for early Brood War, especially since everything being on Korean TV meant Brood War could be hard to read, simultaneously centralized in a small, distant culture and so decentralized across different shows and programs within that culture.

A different time indeed. A time where Nazgul led the competition outside of Korea, but because this competition was so behind Korea, competing wasn’t the main component of his legacy. What was even more important was how he helped bridge the vast information gap between the two.

All or nothing

“A lot of Team Liquid’s heritage is based on being a community website and not a team, right? For the community website it was definitely like feeling people were just not getting what they deserved when it comes to coverage of professional Brood War—something magical to me that was not being shared with the Western community.”

“I mean there were some sites that were trying but were absolute total trash. So I just felt like I can do this better. I know a few friends that can help—some are writers, some are designers, some are coders.”

Core to Nazgul’s motivation is an all-or-nothing feeling. Behind the things he pursues most eagerly, there’s a driving sense that he can reach the highest level if he’s at his best. The counter to that: if he can’t be his best, can’t execute at the highest level, that drive falters. Tough as the mentality sounds, it’s a big part of what pushed Nazgul forward and – later down the line – a part of what would push him out of the game.

(Nazgul talks more about the mindset and quitting StarCraft cold turkey in his TILTS interview above)

“I don’t really celebrate wins, or doing well. I just get miserable over losing; I get miserable over mistakes. That itself is not a super happy part of my personality, but it is my personality. I do embrace it, I do accept it as a reason for why I have done certain things I’m proud of.”

“I’m very, very motivated by the negative. By losing, making mistakes, and then improving off of it.” The mentality of improving the negative was crucial in those earliest days of esports where Nazgul tells me that being on a team only really earned him a few hundred euros a month. Those other motivators aren’t there yet – just love for the game and hate for losing at it.

In those early days Nazgul didn’t even have a sense of being a professional, only a sense of steady progression.

“Honestly, I don’t really know that I tried to class[ify] it that way until much later in my life – thinking back on it. It’s not really like an ‘oh,lightbulb goes on’ moment for me. I mean, none of my career really has been. It’s always just been gradual, just wake up another day trying to be a little better than the day before.”

Equally core to Nazgul is a down-to-earth, simplistic approach to things. Doing things a day at a time and keeping an eye on the process. It’s natural for him to see the levels to StarCraft and to work hard to climb up them – starting with the nascent Dutch scene.

“You work yourself up through the space. First when you log in, you’re in like the Dutch StarCraft channel. I remember being in these Dutch channels coming up and there’d be these legendary names in the Netherlands. Like it’s all of these levels.”

“There would be this group called the Clowns and they were the best in the Netherlands and at some point you think you’re ready to challenge them. You get introduced through a friend, you take a match off of them, and they’re like, ‘holy shit this guy’s good, this guy’s worthwhile practice, I’m gonna play more.’”

“You go through an international level and the same thing happens, right? You get introduced through a friend and you win there. You’re just constantly tracking your own practice partners with regards to, ‘I’m being invited to better and better games.’ Eventually you’re playing with the best people on the continent.”

The odd road to Korea [2002-2003]

Nazgul tells me there were plenty of tournaments and show matches in Europe, some even with small prize pools, but it’s genuinely difficult to track how Nazgul did in the Netherlands and then in Europe. It took me around 200 tabs and a lot of digging to accept that there just wasn’t going to be much record of these tournaments. (Aside from the World Cyber Games, but that’ll come later.)

However, there were other ways to know that Nazgul was rising up the ranks. Namely, his sponsors.

Nazgul’s first ever sponsor was simply a Dutch organization with an interest in the scene and a desire to get their name out. His second sponsor was pG (proGaming), a German organization which was very much a forerunner to the esports teams of the now. From what I can tell, they even hosted tournaments and held videos on their site.

In Nazgul’s words, pG was near to one of the biggest sponsors you could get in Europe at the time.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Was pG the big name and the main force of European esports at that time?

“Yeah. Yeah, I often wonder what happened to the folks that really set that up because they were… I’m not kidding, what I thought was a business opportunity in 2010 and a hobby before that, they thought was a business opportunity in the early 2000’s. I think they had Samsung as a sponsor. […]

“Back then many, many, many of the top StarCraft players were a part of pG. pG Saft, pG Fisheye… […] They were definitely trying and I honestly don’t know what happened to them.”

pro-Gaming was so ahead of its time that the organization even had content creators on board. Dyo made “highlight movies” that were the montages of the day, but also ways to genuinely determine what happened in a notable match or what certain players were doing well. The montage music of the day is also a blast from the past, being much less electronic and a lot more of a certain early 2000’s brand of Metal (Nightwish, System of a Down, etc).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The lost archives, and even the lost organizations, meant that the true measure of Nazgul’s skill was the fact that he made it to the international stage – that he got to play the Koreans at all. After all, it was the Korean scene that mattered. International tournaments were where the Koreans played, the top foreigners played, the top 100 played. These were worth really etching into the annals.

(Many of the promotional and broadcast videos of the time scratch a unique nostalgia itch)

The World Cyber Games (WCG) was the major forerunner of international competition and one of very few tournaments where the focus was to get players from the widest spread of nations possible. They held qualifiers in several countries—including the Netherlands—where the top 2 would qualify for a trip to Seoul, South Korea where the main WCG was played.

Nazgul qualified for the main stage with relative ease, earning him his first chance to compete with the best and his first step on the long journey to Korea. At WCG 2001 and 2002, he proved that he was more than just a big fish in a small pond by beating top foreign players like Fisheye and, more impressively, a top Korean player in Gundam.

In these tournaments, he’d outplaced older legends who had led the foreign scene, like Grrrr, sVEN, Maynard and Smuft. These were both foreign players who had done so well as to move to Korea to compete and genuinely challenge the top talent there. If he’d beaten them, then surely he could follow their path.

His performance in 2001 and 2002 put him up as a rising foreign star alongside Elky—who was on-and-off the best non-Korean player from 2001-2004. In turn, that levelled him up enough that these foreign players living in Korea quickly became more than competitors. They became sparring partners and friends who would help Nazgul up to the next level—Korea.

The nexus of esports

“I’ve always been intrigued with regards to why Koreans were so good at Starcraft,” Nazgul echoes a sentiment that most StarCraft fans at the time had, and many fans still have. In Brood War, Korea’s dominance of the esport was always insanely complete.

“They made up, like, 99 out of the top 100 players. That’s how good they were.”

It made sense to be enamored then, much in the same way that a strong subsection of western League fans devoutly watch the LPL and LCK. To be enamored from the mastery of a craft – seeing a thing done the way it’s truly meant to be done.

But at the time it also made sense in a deeper, more cultural way, where Korea had created lines of infrastructure and market penetration that you’d never see in the West. More than just being on TV, StarCraft in Korea had government support and regulation in KGPA and then KeSPA, and top StarCraft players had enough popularity to cultivate fandoms.

However the West reached for what Korea had, they’d only end up with a pale imitation.

Though many people like to highlight cultural differences, the West’s lagging behind wasn’t due to lack of spirit. Nazgul stresses that a great deal of work went into TL.net and it all came pouring in through volunteers who knew there was no pay in sight for this.

Moreso, it was many other strange turns of fortune that propelled Korea forward. Things like a large PC culture built around net cafes (PC bangs), a lack of interest in consoles, and even size. Surely, it’s easier to play online and coordinate offline in one small country than in one large continent.

It was also socio-economic confluences, great lines of aggregate supply moving like mystical force, which propelled Korea forward into this niche. Things like the 1997 Financial Crisis also pushed Korea into supporting burgeoning tech and communication sectors more than they already were and certainly more than the West was. Put the strong investment in with the PC bang industry and Korea was a big step ahead of the West.

For foreign players in the beginning of Brood War, Korea was the pro gaming dream made real. By the time Victor went to Korea in the second half of 2002, the dream had become a surprisingly real path.

“In that moment it was more organic than you would think. It just made sense. What made that one in particular for me was that I knew Elky, as a French player, was already living in Korea, that was really important for me. Smuft, a Canadian, was living in Korea as well.”

“What made it so organic was them just being my practice partners and being like, ‘Oh yeah, you should live in Korea! It’s no problem, it’s fun. Just get yourself an apartment.’ To me, it all felt pretty natural.”

By the time Nazgul reached his peak in Europe, It had become so strangely natural for foreign pros to go to Korea that there were even forum posts about it. TL.net users would hop and either ponder idly or ask openly if the one and only Nazgul would join Elky and company there one day.

Nazgul stresses the fact that by the time he went, Foreign players like Grrrr hadn’t just paved the way, they’d settled down and set up shop.

“Guillaume [Grrrr] was already there two years before I came. I mean, that was mind-blowing with regards to how early he went there, on his own. He completely mastered the language of Korean, he still lives there today as far as I know, and speaks it fluently.”

More than mastering the language, Grrrr would really take the country on as his own home, eventually becoming something of a TV star, settling down, and getting married. By the time that Nazgul arrived in 2003, Grrrr’s StarCraft was already beginning to wind down. Nazgul knows in advance that all the early era Brood War players fall into the same, almost mythic categorization but when Nazgul was in his prime, Grrrr was the old legend.

“I know right now it feels like, ‘Wait, weren’t all you guys early in the game?’ No. […] Guillaume was like a legend who almost, with his ability from years before was still doing okay in the now but more thriving on this natural talent and instinct for the game rather than being completely up to par with the mechanics of that day.”

“Mechanics surpassed me eventually too,” he’s quick to add, “but the same thing with folks from three years before that.”

For a lot of casual fans and observers, this is an important reminder that over the early eras of sport, it’s not as simple as writing all legends off as similarly bad or good. It’s not as simple as watching old Brood War videos and spotting out dirty micro and bad macro. The game was evolving then as it is now, always forcing adaptation and churning through those couldn’t keep up.

If Korea really was the nexus of Brood War, the path to reach it was brutal.

A brutal path [January-February 2003]

For starters that path wasn’t available to all or even most of the world that walked the way of the Brood War pro.

This is not the modern day where even individual NA League players can save up the money to bootcamp in Korea in the offseason. If you were foreign, you had to be great to get to Korea. In most places, there wasn’t the money to be sending over mediocre talent and even the good players could spend years lurching inside qualifiers to make it into one of Korea’s competitive leagues.

StarCraft being so popular only made things harder, the esport booming out well in front of infrastructure, sponsors, and market value. Competition quickly outgrew opportunity. Even competitors in Korea struggled to make a living, as shown by a player strike that pushed for higher pay on television appearances. The response from companies was that the money wasn’t there yet.

Despite all of this, Nazgul made the beginning of his journey look relatively easy.

When Nazgul made it to Korea, on top of pG he’d gotten another even bigger sponsor in AMD, the processor manufacturer and tech company. He was part of what was called the AMD Dream Team (featuring Elky and Grrrr) and had a manager who handled stuff like TV appearances, sponsor work, scheduling, transportation, and so on. They hadn’t quite set up a team house, so to play with the team Nazgul would take a subway to Elky and Grrrr’s apartment.

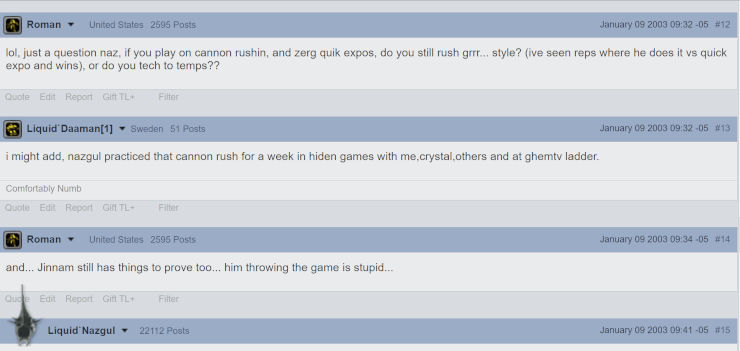

His first big televised match would be a showmatch on a program called About StarCraft 2003 against JinNam—a Korean Zerg player who had a strong end to 2002. JinNam had even managed a win against Boxer in November 2002 (Boxer was likely the world’s best player and touted as The Emperor of Terran).

JinNam’s results seemed to have fallen a bit since then and he may not have been a top 10 caliber player—but he was strong. Strong enough that some of TL.net’s veteran voices felt it rough this would be Nazgul’s first match. This was also partially the design of the About StarCraft—a show that focused on an established pro (JinNam) and then pitted them against a newcomer (Nazgul).

Inherently the underdog, Nazgul came prepared. He whipped up specific early game strategies that he used to build an ever-mounting lead over JinNam. Nazgul had his opponent in a complete chokehold, having more resources, upgrades, and supply—only to have his lead snatched from him by the game crashing. He wrote in a later battle report that the production team planned to give him a victory by decision, but couldn’t because the replay wouldn’t load.

Nazgul recalls the crash as even more disastrous from a strategic lens. “It was one of those games where I’d prepared something really specific that you can only do once, and so that thing was winning the game. And the crash happens and I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I’m screwed now.’ You have this big surprise play up your sleeve and it’s gone.”

(According to another top European player and Liquid clan member, Daaman, he and Nazgul had secretly practiced this strategy for a week.)

Despite the disaster, Nazgul won the runback using a similar strategy but with variations on the details. The second win spoke well to Nazgul’s strength as a player, being able to rework the strategy a bit on the fly and still pick up a big win without the element of surprise. Nazgul would lose his next match on About StarCraft to the Terran, Lee, but it was likely valuable matchup experience in the end.

As the first month of his trip was coming to an end, it looked like the fun would soon be over. Nazgul was set to participate in one of the earliest team leagues, which pit teams like AMD against others in what’s almost a kind of relay race or crew battle where each team sends a player out to 1v1 another. As a part of the pre-season he’d face off against XellOs.

If XellOs wasn’t a top 10 player worldwide at that moment, he was damn close—and he’d be top 5 by the year’s end. Nicknamed “Perfect Terran,” XellOs was defined by immaculate, clean play and was already on his way to having an insane year where he’d beat Boxer and a number of other top players. The mood on the forums was less than optimistic.

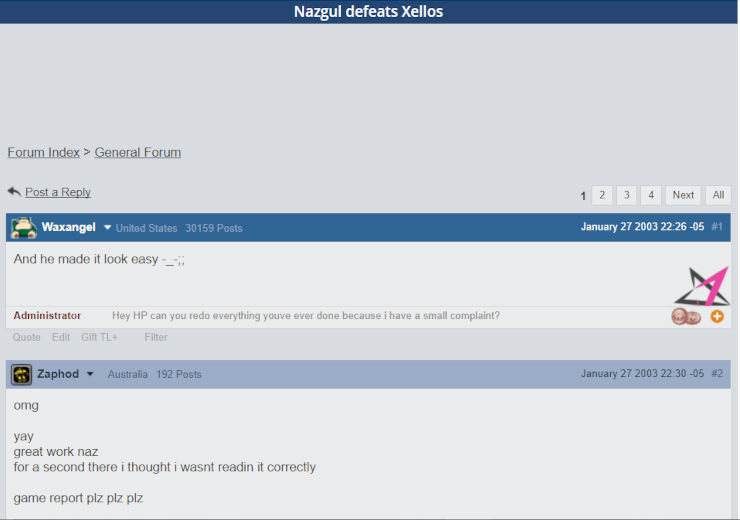

The news of the result came in the way that it always did back then – a thread on TL.net.

The topic read: “Nazgul defeats XellOs”

Underneath, in the body: “And he made it look easy -_-;;”

Posted by waxangel, the now editor of TL.net, he’d follow that result with a battle report that was more detailed than the standard of the day. This report is longer than the rest,” wax wrote, “because everyone here seems to care so much about Naz.”

In the Western community, Nazgul was beloved—a genuine fan favorite. It’s a sentiment that was obvious enough to joke about at the time but even the obvious things can go forgotten and buried. At the same time Nazgul was a player, he was also a community voice and leader.

This was a player who not only replayed his match against JinNam but rewrote his own in-depth battle report of that match after it got eaten by the html. This was a professional player with thousands of posts, someone who’d developed an instant rapport not just through admirable skill, but through helping to create and run one of gaming’s largest community websites at the time.

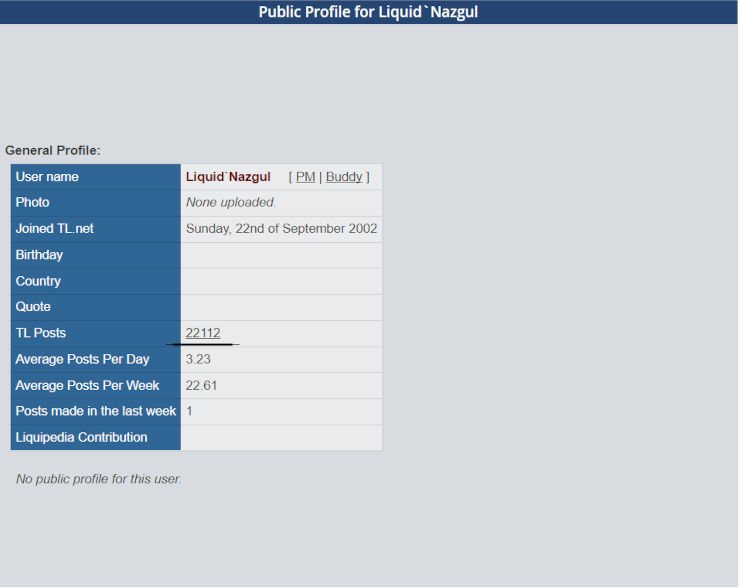

Hell, Victor the Co-Ceo is still posting and has over 22,000 posts today. In my community boards experience, we’d call that person a spammer. A part of what made Nazgul special as a player was that he was never just that.

Shortly after, Nazgul would qualify for one of the biggest leagues in Korea – the Ongament Challenge League (OCL). Even if everyone was rooting for him, given how brutal this mecca’s pilgrimage was, Nazgul had still surprised pretty much everyone but himself.

Were you surprised by that [XellOs win] at that moment?

“No, I wasn’t really surprised but I don’t know that that’s unique to me. In most sports if you wanna make it to the top you have to have a pretty relentless self-belief. For me I definitely felt like I could and would beat players like that given the right opportunities. […] It was a big accomplishment. There was definitely a sense of accomplishment.”

Nazgul’s voice trails down a bit, “I would’ve liked to have done a bit more of it, though.”

Running out of steam [March-April 2003]

In Brood War, StarCraft, and most 1v1 sports with heavy tournament schedules, reaching the top is only part of the challenge. A bigger part is staying there.

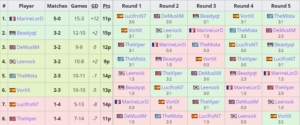

Nazgul had gotten off to a great start not only by beating JinNam and XellOs but by qualifying for the OnGameNet Challenge League (OCL), the tournament that fed into the grandest Brood War competition of them all: The OnGameNet Starleague (OSL). In the OCL itself, he’d face opponents that were lower caliber and go in with much higher standing. His first opponent, Classic_NT, was a rookie somewhat on the rise and his second, SaferZerg, was a Zerg main with a successful career that had been doing well in the year.

According to a battle report by a prominent TL.net writer and community member mensrea, the casters even favored Nazgul to exit the group in first if he beat Classic_NT. In early Brood War, with the game so undiscovered and the competition so deep, it’s always “if.”

This time, Nazgul was on the receiving end of an early game strategy as Classic_NT rushed marines, medics, and tanks – a strong offensive combination of range, mass, and healing. Nazgul had built a nice wealth of Dragoons (strong and flexible Protoss units in the early game) and in one moment seemed like he’d stave off the advance.

However, mensrea and a number of other commentators note that Nazgul’s micro (or execution) was off. He didn’t seem to be controlling his units well and from watching what few other available VODS there are, the analysis lines up. Dragoons have a great utility in form of range, being able to kite out. They’re vital in the early game in the Protoss vs. Terran (PvT) matchup and in other games Nazgul had microed them well enough to handle tanks or marines. Not here. Having lost too much too early, Nazgul concedes.

In his next game, he’d face SaferZerg where he’d put up a considerably better fight. However, SaferZerg won the war over expansion and hemmed Nazgul in, building up a better economy, better control over the map, and ultimately a better army. When the late game rolled around, Nazgul lost SaferZerg’s larger army.

Following these two defeats, Nazgul would fall out early in two preliminaries—though, to two very strong opponents. He fell to kOs, a Terran who had beaten JinNam, Reach, and taken a game off of Boxer. Then Nazgul later fell to JJu, a rising Zerg talent. Nazgul managed to take a game off the latter, which albeit impressive, wasn’t enough to qualify for the next league and wasn’t enough for Nazgul.

“For a period of one to two years I think I was arguably the best player outside of Korea. When I went to Korea, now if I think back it’s like, ‘I won 50% of my professional matches, qualified into Ongamenet Starleague on my first try…’ There’s other players that lived there for three years before qualifying for their first time. So now I think, ‘Oh maybe that was as bit of a special moment!”

“But if I think back, the feeling was actually, ‘Wow, I failed!’ Because I lost in the first round of the TV matches. It wasn’t, ‘Oh my god, look at me I qualified!’ I expected to qualify and losing was disappointing. It wasn’t some amazing moment. […] I was unhappy with anything that wasn’t to my standards.”

New hands and familiar declines [April 2003-]

Nazgul’s brand of perfectionism and all-or-nothing style had gotten him up to this apex but it wouldn’t match well with the reality of the situation. Running out of money in his early 20’s, future looking hazy, it wasn’t clear that life would let Nazgul stay the StarCraft course at all—let alone play his best game. For him, it wasn’t growing old and slowing down that was the trouble—it was growing up and needing income and security.

“For years on end people have been writing, ‘Oh if you’re 22 years old or 23 years old you can write yourself off as an esports player.’ I’ve never believed that to be true. I always believed that was related to economics because if you’re making nothing, or close to nothing compared to having a job, then once you hit 21 you better start thinking about some different things.”

“In Korea, I was like hey I got to figure something out with regards to my life. Don’t really know what, but obviously I can’t really keep doing this. So I went back to the Netherlands, I went to study International Business Administration. I started playing Poker and so in that period I stopped playing as much.”

For those that know Brood War this is a very familiar end to a pro career. Just knowing older esports scenes means it’s not novel. In the early, underfunded days of competition only very few athletes could make a real, livable wage from esports. Living off the passion of the game could work in the teen years but adulthood sets on fierce in the 20’s and that need for financial security mounts.

Despite his gearing down directly after returning to the Netherlands, Nazgul’s form remained sharp. “I think I still won WCG Netherlands 2003 [the regional qualifier for WCG 2003] – I was still in pretty good shape.” Nazgul shapes out the gradual slope of the decline. “Then in 2004 I think I won it again, but that was not really playing for a year but then practicing a month before. And then after that it really, really slowed down.”

He qualified for both WCG 2003 and 2004 but didn’t escape groups at either event. In both years, he was still managing to take games—and even sets—off of strong Foreign players like Rekrul, Hellghost, Socke, Fisheye, and Elky. He won some notable tournaments too, like AMD pG Challenge Summer 2003, the first and third Team Liquid Invitationals, and helped the Netherlands team go far in European competitions.

It is enough for Nazgul to wonder if he didn’t have a few good years of prime Brood War in him that he simply didn’t get to play out. “I really quit because of life reasons. For StarCraft, I feel like I stopped when I was at my best.”

“My speed was still my weakness,” Nazgul admits, referring to his actions per minute (APM). High APM is key to a lot of the absolute highest echelon of players in both Brood War and StarCraft 2 now and like many older era players, Nazgul’s APM wasn’t the best.

“I was of medium speed outside of Korea, probably lower speed in Korea. APM was not the reason why [I retired]. I could’ve played at the top for much, much longer with my speed. But if you look like 4, 5, 6 years after my time, then you’re hitting speeds that I never could have competed with even if I continued.”

Still, he was getting outpaced by newer and younger European talent like Mondragon or Ret. He was also growing up and taking on a new hand that the world had bizarrely dealt to many a retired Brood War pro: Poker.

Grrrr, Elky, and many other Brood War pros had taken to online poker as a new form of competition. One which was more financially viable as well. Grrrr and Nazgul would both have solid poker careers before transitioning to other things while Elky is still a very accomplished poker player.

This was because, with the advent of online gambling, poker in particular was hitting its own new era of play. One that StarCraft players were surprisingly well-suited for.

“When you play Poker,” Nazgul explains, “the money you earn is your working capital. So you start with low stakes, you start winning, if you cash it out, that means you have no money to go to the next stakes.You wanna keep going up, you wanna keep levelling, playing higher and higher tables.”

If you’re feeling deja vu, you might be remembering Nazgul’s earlier words about the feeling of levelling up in StarCraft and playing higher and higher level opponents.

“The money online, I think to at least my generation of poker players, felt fictional. It felt like points in a game that would get you to the next level.”

“If you think of all the different games out there, I don’t think poker is the most similar to StarCraft but the similarity is like, you need to put in the hours, you need to self-evaluate, you need to have strategic reasoning. […] When we switched to poker it’s like this intersection between people who learned poker in live casinos and bars in the United States and stuff.”

“And then there’s like a new generation that would be playing like ten to twenty tables online and playing massive amounts of hands and looking at it like StarCraft, and laddering up.” Asking Nazgul about it, he confirms that the online world even gave his generation of players an advantage. “Old school poker players, maybe they looked down on it, but they couldn’t cope with playing 15 tables at the same time, learning at a rapid speed, doing all this stuff at the same time.”

He says that with no glee or remorse either, as newer poker players eventually beat him out too. “And then eventually, after like 5, 6, 7 years of my career there were other advancements in terms of using software and analytical programs and statistics. For me, I was always playing based on feel and not looking at statistics and numbers.”

“Then you have this clash of the early online players who are not using statistical programs versus the newer generation who are. For a while I was like, ‘Well, that’s all nonsense. I can easily beat it.’ Turns out you can’t.”

“I’m definitely a victim of, at some point you start believing yourself a little too much and you stop reinventing. That’s what happened with me in Poker.”

If playing 15 tables and rapidly intaking diverse sets of info sounds like StarCraft’s fast game of information asymmetry, then the rising statistical modelling probably ought to sound like the ways StarCraft pros squeeze the game via APM, macros, and innovation. Nazgul found that his time as a competitor in both spaces ran out.

But his time as a community leader never stopped. Running TL.net all the way up to StarCraft 2’s release, he’d transition fully into that leadership role and follow the opportunity to build TL out from clan to website to professional team—keeping the community aspect intact all along the way.

He tells me that, by the time he was competing in StarCraft 2, he had little to no desire for destroying the competition or grinding up to the top. He just wanted to put the hours in to understand the game deeply enough to scout players, scope out events, and understand the community. His golden age in the competitive sense was long gone and he was chasing a new golden age for Team Liquid.

After the Curse merger, the 4 LCS titles, the fastest CS:GO Grand Slam in history, the TI title, the longest concurrent number 1 run in Melee history, and whatever you want to call Rapha’s insane dominance over Quake—there’s no doubt Team Liquid has had its golden ages.

It’s those golden ages that slowly transition Nazgul into Victor, less the player and more the leader, team owner, and person. But there’s a value in looking back at Nazgul, the young Dutch competitor whose run was simultaneously emblematic of the struggles of a foreign player in the early years of Brood War and unique enough to be a story all his own.

Writer // Austin R. Ryan

Graphics // Zack Kiesewetter