If it’s possible to be an institution and an outsider at the same time, then Jeff Minter is both. He is, perhaps, the last of the original lone gunmen in video games. As a self-taught teenage coder, he joined the explosive homebrew game development scene in the U.K. in the early 1980s, cranking out surreal home computer games inspired by the arcade classics, mostly on his own. Unlike most of his peers from that time, he has been doing pretty much exactly that ever since. For 40 years.

His latest game, the newly released Akka Arrh, reunites him with Atari, the company with which he made one of his most famous and brilliant games: Tempest 2000, a pounding, techno-infused 1994 reinterpretation of an already hypnotic 1981 arcade machine. Minter and Atari have had their ups and downs over the years, but something keeps drawing them back together. In this case, it’s a rare, unreleased arcade game that was thought lost for many years, and was rumored to be too difficult to release.

“There was only one guy who had a working copy of it; he had a coin-op and wouldn’t release the ROMs,” Minter tells me over a video call from Wales, where he lives in rural isolation, with a flock of sheep, a llama, a donkey, and his partner in life and work, Ivan “Giles” Zorzin. (Minter loves llamas, and also camels, sheep, moose, goats, and ungulates of all kinds, and takes every opportunity to put these animals in his games. His company is called Llamasoft.) He’s an affable, scruffy, 60-year-old longhair from the English Midlands with the sense of humor of a generation raised on Monty Python and recreational drugs: the sort you’d expect to find down the pub in a leather coat, talking about obscure prog rock. Behind him I can see disorderly piles of game controllers and musical equipment, guitars, and a poster for his 1983 game Attack of the Mutant Camels.

Anyway, back to Akka Arrh. The ROMs eventually got out — liberated by “somebody else who was maintaining [the guy’s] machines” — and you can now play the game (alongside Tempest 2000 and many other classics) as part of the excellent Atari 50 compilation. It’s a curious design: The player controls a turret in the center of the screen, destroying oncoming enemies by using shots to light up the petals of strangely beautiful, lotus flower-like designs. If enemies get too close, they invade an inner sanctum, and the game’s central (and rather aggravating) gimmick involves switching between these two levels to repel them.

[embedded content]

Minter liked the look of it, and when Atari offered him the chance to adapt anything from its back catalog, it’s what he picked. But this was not the same task as remaking Tempest.

“It’s not so much that it’s really hard,” he says. “It’s that it’s not really engaging enough. Basically, the thing failed its field test, and I don’t think it’s for as simple a reason as it being too hard.” The game overwhelmed the player quickly, but so did classics like Minter’s all-time favorite, Eugene Jarvis’ Robotron. The problem was that it just wasn’t appealing enough to bring the player back. Something was missing.

The search for that missing something took a long time. “I had to do quite a bit of surgery on it, really,” Minter says. He slowed the game down to make it more palatable for home play, and started fooling around with the design. Minter works in an improvisational way, iterating on the design live in the code.

“I have to feel it, basically,” he says. “With this, I was working with various different ideas for how the game might work, how I might improve it, and I was getting nowhere for ages and ages and ages. It was after several months I finally made a breakthrough.”

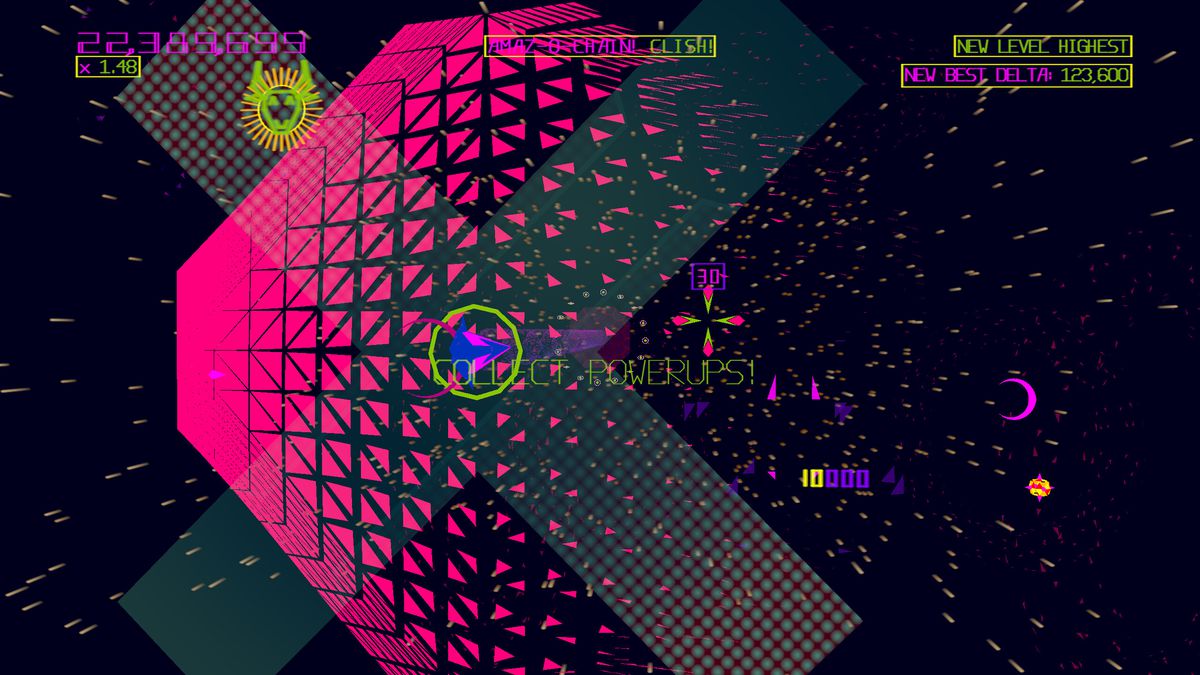

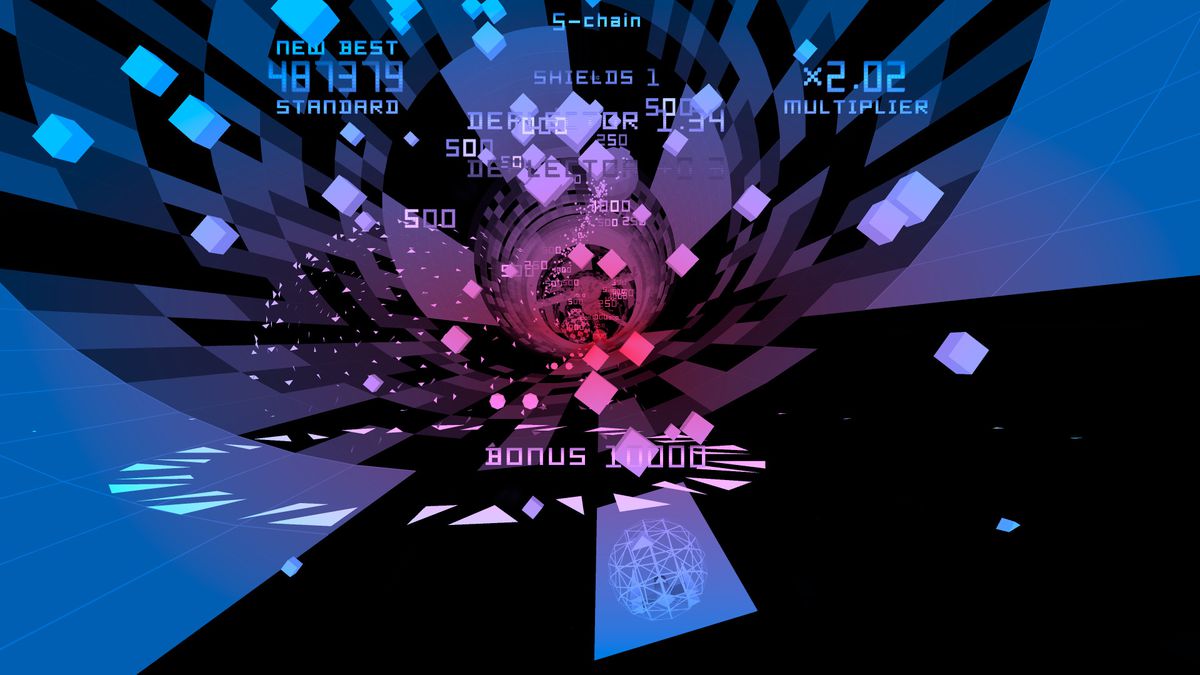

What he came up with is a daring inversion of the kind of frenetic arcade games he is known for: a “cerebral shooter, almost like a puzzle game.” Rather than lighting up panels to destroy enemies, the player releases bombs that trigger chains of detonations, Missile Command-style. Each new bomb resets the score multiplier, so the idea is to use as few as possible. Each enemy killed with bombs earns you bullets that can be used to down a different kind of enemy. Bullets don’t reset the multiplier, but they are in finite supply, so they need to be used just as carefully. The new Akka Arrh is an arcade shooter in which you need to shoot as little as possible.

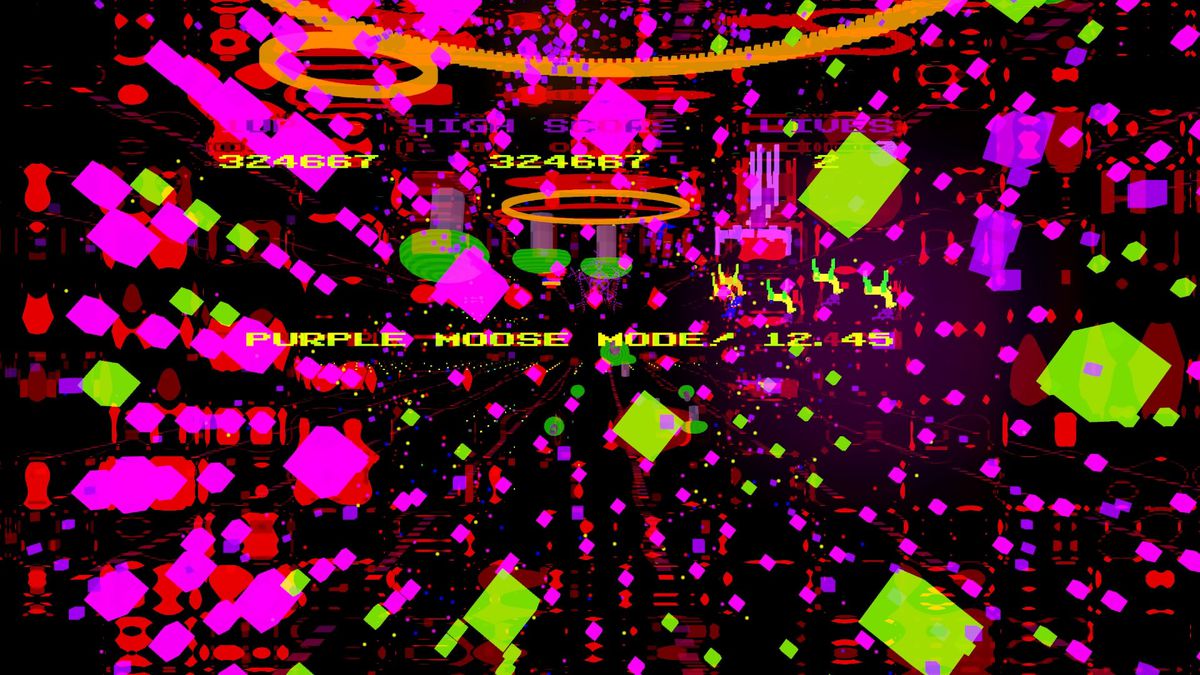

Minter also made the game “more asymmetric,” so enemy invasions on the lower level became sudden, brief bursts of frenetic action set to high-BPM techno, contrasting with the measured tactical gameplay upstairs, which is scored by a more dreamy, abstract musical signature. It’s a deeply strange and engrossing game — much more mindful, layered, and complex than the original, and indeed than most of Minter’s output. Each level is a conundrum to solve as much as gauntlet to survive.

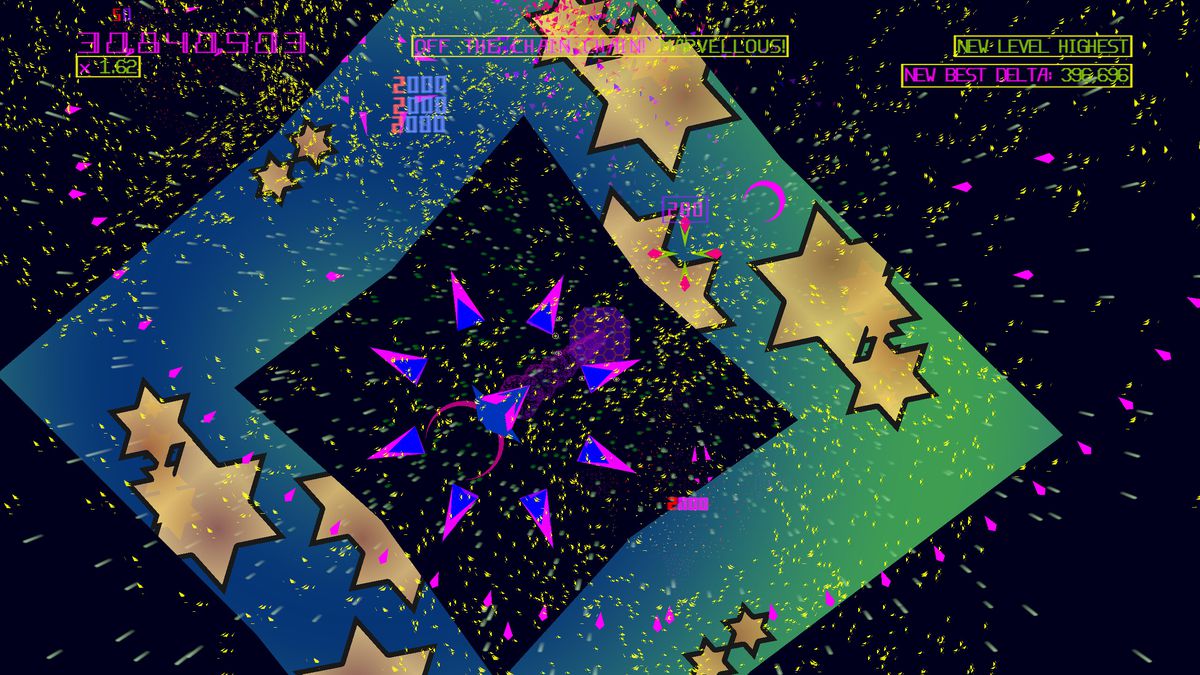

That’s not to say it’s not instantly recognizable as a Minter game, though, from its eye-watering, strobing neon color scheme to the scrolling text offering tips and obscure witticisms, and the general invitation to the player to enter a psychotropic zen state. Over four decades, Minter has made dozens and dozens of games like this, but Akka Arrh is one of the most distinctive, and best.

It wasn’t a given that Minter would ever work with Atari again. After Tempest 2000, Minter moved to California to work at Atari for a few years, but hated it.

“You can tell I didn’t like it, because I went out there in 1994 and I came back in 1997 just to live in Wales with the sheep again, and do my own thing again,” he says.

The iconic gaming brand has been through quite a few hands and changes of management over the years, and the people who control Atari haven’t always treated its creators well. After playing some of Minter’s games on home computers as a kid, I next encountered his work with Tempest 2000 — only not. Minter’s game was for Atari’s Jaguar console. The PlayStation game I played was called Tempest X3, which was a bit of a middle-finger to Minter.

“I made one of the bestselling games on the Jaguar, and by way of reward, Atari changed the game just enough to cut me out of any royalties, and then released it on a much more successful platform under a different name,” Minter laughs ruefully. “I actually spoke to the programmer, several years later, and he told me he’d been specifically instructed to change it just enough to ‘reduce the royalty burden.’ Now isn’t that lovely?”

Llamasoft’s Tempest 2000, Space Giraffe, Moose Life, and Polybius.

Minter couldn’t leave his classic alone, though. He made a sequel, Tempest 3000, for the obscure Nuon platform. He riffed on the idea for the visually dense and chameleonic Space Giraffe on Xbox 360. In 2014, perhaps as revenge for Tempest X3, he made a (superb) unlicensed spiritual sequel for PlayStation Vita called TxK. Atari wasn’t pleased, and threatened him with legal action, blocking further releases on other platforms.

It’s surprising, then, that Minter and Atari have been able to overcome all this bad blood. He’s not exactly forgiving, but he is pragmatic about it.

“At the end of the day, it kind of makes more sense to work with them than against them, doesn’t it?” he says. “And I enjoy working on some of their back catalog stuff. There’s some nice stuff there to play around with. And at least I can do it in such a way that I get paid now.” The two parties agreed to resolve their differences over TxK and turn it into an official sequel, Tempest 4000. “I wasn’t going to pay them any money anyway. I didn’t have any money to bloody give them, what are they gonna do?”

Minter says he struggles to make enough money from Llamasoft’s self-published releases of his original games, and has to deal with marketing, which he hates. Accepting commissions from Atari, he doesn’t have to think about any of that, and gets paid by the milestone. He dreams of making enough money this way that he can self-fund his dream project: Space Giraffe 2 in VR.

“Space Giraffe is probably the best thing we’ve ever made,” he says. “And to actually bring it into virtual reality would be the convergence of everything ever done in my entire career. Then [I could] collapse in a heap, exhausted and tired.”

Does he mean retirement? “I’ll never fully retire. I’ll always be making something. It would just be nice not to give a toss about bloody money anymore.”

It’s telling that Minter can’t imagine a world in which he’s not coding. He’s been making these games his whole adult life, and they’re deeply personal to him. He’s drawn to the games’ abstraction because he’s bad at art, but good at describing things mathematically and procedurally, and he loves creating flashy effects. “I like to strive for unreality!” he says. “The thing I most like about virtual reality is when you can get as far away from real reality as possible.” But his games are anything but impersonal, because he floods them with his own voice, addressing the player directly in snippets of text that express his sense of humor.

“I love doing that kind of thing!” he laughs. “There’s a few I had to take out of this one, actually. If you scored no points on a level it would say that you scored Boris Johnson’s integrity. But the political stuff, I had to take out. I’m just having a bit of fun with it really. […] It’s just me, dicking about.”

Along with games, Minter has long written trippy music visualizers. He wrote the one found in the Xbox 360 dashboard, and enjoyed a rivalry with others on the visualizer scene. Users of the old PC music player WinAMP may remember its audio test file proudly declaring, “It really whips the llama’s ass!” That’s a reference to Minter.

“Yeah, that’s my obscure claim to fame,” he says. “I am the llama. And my arse is getting kicked, apparently.” (His other obscure claim to fame is providing the visuals for a Nine Inch Nails song with his game Polybius.)

[embedded content]

Asked about his love of the animals, Minter gets a little uncharacteristically shy and sentimental. Their appearance in the games started as a joke — replacing the AT-ATs in a clone of a Star Wars game with camels — but he seems to have a genuine spiritual connection to the beasts.

“If you treat them as companion animals instead of livestock, then they’re just as companionable as a cat or a dog, really,” he says. “They’re also very calming to be around. If you feel a bit stressed out, you can’t really feel stressed out when you go outside and a big wooly sheep comes up and needs cuddles.” He talks wistfully about recording his sheep Jerry’s bleat and putting it in his games. “Jerry’s our oldest sheep. He’s over 15 years old now, which is an old age for a sheep, and he’s just lost his brother. So yeah, it’s just nice to have his ‘baa’ in there, and in years to come I can hear that and I can think of Jerry.”

In a sense, Jeff Minter has always moved with the times. He’s been an early adopter of many technologies, from DVD media to smartphones and virtual reality. But in another sense, he’s remained frozen in a moment in time: refusing to believe that his games, or the way he makes them, really need to change from that magical moment in the early ’80s when he started. A moment when anything seemed possible, and when a new art form was materializing in front of his eyes.

“It was just wonderful,” he remembers. “You’d go to the exhibitions, and you’d meet the people who played the games, and you’d meet the other programmers and go in the bar, get pissed with them, or go outside and have a spliff with them. It was just amazingly naive and creative days, really. It was all so new.

“I often describe it as being like: Imagine if you lived in a time before there was music, and then during the course of your life, somebody discovered music. And the first people were singing songs and forming bands. Imagine how amazing that would have felt! That’s how it felt back in the early days of this. And it came out of nothing.”

Akka Arrh is out now on Atari VCS, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4 and 5, Windows PC, and Xbox Series X.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.polygon.com/23613576/jeff-minter-profile-akka-arrh-atari-llamasoft-arcade

- 15 years

- 1980s

- 7

- About

- ABSTRACT

- Action

- adapt

- Addressing

- Against

- All

- alone

- alongside

- amazing

- animals

- Another

- Anything

- Arcade

- arcade games

- around

- Art

- as

- Asymmetric

- Atari

- audio

- bar

- beautiful

- because

- before

- behind

- believe

- BEST

- bestselling

- between

- BIG

- Bit

- Blizzard

- blood

- Blue

- bomb

- brand

- breakthrough

- bring

- burden

- california

- call

- Career

- carefully

- case

- catalog

- Center

- central

- chains

- chance

- change

- changes

- claim

- Classic

- classics

- code

- Coding

- collapse

- collect

- colorful

- commissions

- company

- complex

- computer

- Computer games

- computers

- connection

- Console

- content

- Control

- Controllers

- controls

- could

- course

- Creating

- Creative

- Creators

- Curious

- Cut

- dashboard

- day

- deal

- decades

- Design

- designs

- destroy

- Development

- device

- DID

- different

- difficult

- discovered

- dog

- down

- dozens

- Drawing

- dreams

- Drugs

- During

- Early

- Edge

- embedded

- engaging

- English

- enjoyed

- Enter

- equipment

- EVER

- Every

- everything

- exactly

- Exhibitions

- expect

- eyes

- Failed

- FAME

- favorite

- field

- filled

- Finally

- First

- floods

- form

- front

- fun

- further

- game

- gameplay

- Games

- Gaming

- General

- generation.

- getting

- given

- going

- good

- hands

- Hard

- hates

- having

- head

- hear

- Home

- homebrew

- How

- HTTPS

- Humor

- i

- idea

- improve

- inspired

- instead

- Institution

- isolation

- IT

- jaguar

- joined

- K

- kind

- known

- last

- latest

- Legal

- Legal Action

- Level

- levels

- Life

- light

- Lighting

- Little

- Live

- lives

- Llamas

- Long

- love

- machine

- make

- MAKES

- Making

- management

- Marketing

- May

- Media

- might

- milestone

- missing

- money

- months

- Moose

- more

- Music

- musical

- Mutant

- need

- needs

- Neon

- New

- Nice

- Nine

- Nintendo

- Nintendo Switch

- offering

- official

- Old

- oldest

- One

- Opportunity

- original

- Other

- Others

- own

- paid

- palatable

- panels

- part

- particle

- parties

- partner

- Pay

- PC

- People

- personal

- Picked

- platform

- Platforms

- plato

- plato data intelligence

- platodata

- platogaming

- play

- player

- Playing

- playstation

- playstation 4

- Playstation Vita

- pleased

- Points

- political

- Polygon

- possible

- pretty

- probably

- Problem

- project

- putting

- Puzzle

- puzzle game

- quickly

- quite

- raised

- Rare

- Real

- Reality

- Recreational

- release

- released

- Releases

- Remember

- Resolve

- retirement

- revenge

- reward

- rivalry

- Rock

- Royalty

- Rural

- scheme

- Screen

- Search

- seems

- sense

- sequel

- Series

- set

- several

- shaped

- sheep

- Shooter

- Simple

- smartphones

- So

- SOLVE

- something

- specifically

- Star

- Star Wars

- started

- State

- strive

- successful

- such

- supply

- surgery

- surprising

- survive

- Switch

- tactical

- Take

- talking

- Talks

- Technologies

- Teenage

- tells

- test

- text

- The

- The Game

- thing

- things

- Through

- time

- times

- tips

- together

- toss

- treat

- trigger

- U.K.

- under

- up

- UPS

- users

- various

- VCs

- via

- Video

- video games

- Virtual

- Virtual reality

- Vita

- Voice

- vr

- wales

- well

- What

- WHO

- Wikipedia

- windows

- Windows PC

- Work

- working

- works

- world

- X

- xbox

- Xbox 360

- xbox series

- Xbox Series X

- years

- youtube

- Zen

- zephyrnet