In the broader fighting game community, but in the Guilty Gear community especially, there’s a running joke that if you sit down at the setup and your opponent is a trans kid, you have no chance of victory. That kid is an absolutely insane player and you are about to be destroyed by combos and mix-ups beyond your imagination.

It’s a widely-told joke because of how real and unreal it is.

Guilty Gear is a once-niche, now incredibly popular series of anime fighting games. Its newest edition, Guilty Gear Strive (GGST), regularly headlines national fighting game tournaments and attracts entrants from all corners of the fighting game community (FGC) — including Smash Bros. At the national level, at the regional level, at the local level, queer players aren’t just a part of the scene, they are both the bedrock and the summit.-

That’s the real side of the joke. The unreal side is that this is all incredibly unusual. Sure, in most competitive gaming and esports spaces, you‘ll find queer people and players — and even many large, traditionally very straight-catered scenes are trying to be more queer-friendly. But very, very few esports have the level (and depth) of representation that Guilty Gear, Smash, and the wider FGC do.

As a queer person, it’s something I’ve loved so much about the space that it makes it more difficult to return to other esports scenes. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve had many good interactions with pros, commentators, and community leaders in a ton of scenes — and I’ve seen the effort made to make their spaces better for LGBTQ+ people. But I can count the number of queer top players in most tier 1 esports on one hand, while in the FGC and Smash, there are so many strong queer players that I often don’t think of them as “queer players” at all. They’re just part of the community. I’m just part of the community.

It’s a great feeling, but such a unique one that I can’t help but interrogate it. I can’t help but ask myself: Why is the FGC so queer?

This year, I decided to get more of an answer. So, I asked around, and talked with four notable LGBTQ+ leaders in the FGC:

- Jessika “Romolla” Neva, a top Guilty Gear player, content creator, and cow v-tuber.

- Sasha “Magi” Sullivan, a top Smash Bros. Melee player and content creator.

- Dara “Dara” M. Gar, a top Smash Bros. Ultimate commentator

- Josh “Jaaahsh” Marcotte, a lead TO in Smash 4 and Ultimate (and current Talent Manager in Liquid)

But before I get into the question and answer, I want to get into why they matter. Traditionally, this is something you save for your conclusion. Your grand finale. But this is something you need to understand— not as you leave, but as you go in.

Weights off // life-changer

In 2019, Romolla had the best year of competitive Guilty Gear in her life, up to that point. She placed top 8 or higher at 6 major tournaments, beat a number of NA’s best GG players, and won EVO — one of the most prestigious events in the FGC. When Romolla won EVO, she did so under her old tag, but with a new identity. Though the GG scene didn’t know it yet, Romolla was already transitioning. –

“I wasn’t publicly mentioning it, but I was on hormones for a week before I won EVO,” Romolla chuckles. “Everything EVO on, I probably overperformed just because I was feeling a lot better. That probably is why I had a bit of a peak. […] I would almost directly contribute it to even the placebo of being like, ‘Oh, I’m just on [HRT], and I don’t have to think about it.”

“It was game-changing,” Romolla says, then swiftly amends, “It was actually a life-changer.”

[embedded content]

What Romolla’s saying here, is both unique and shared — like a lot of aspects of the queer experience. Magi didn’t feel that she overperformed or improved when she came out to her scene, but her coming out was undeniably a life-changer and a weight lifted. It was something that turned an already important pursuit into a main mode of expression.

“The Smash scene — that was everything to me. […] I’d never found a career that had made sense to me, I had no passion for like anything in the world besides Smash. And on top of that, it was the only space that I could really be myself in, right? So it was completely integral to my sanity.”

What’s telling is that Magi says this even though, aside from her identity, her childhood was very good. “If you literally were to just take out the queer part, my child, it’s like, nearly perfect.”

But the weight of having your identity questioned, forbidden, or locked down is so heavy that, for Magi, time was measured in the moments she could take it off. “There was definitely a period in my life where time felt like the distance between Smash tournaments.”

This is what so much of trans rights, gay rights, and Pride is truly about. Not illness, not tragedy, not a desire to spread an agenda, not even truly a desire to judge and condemn others for their lack of understanding. What this is about is something that the FGC has long been about — finding your full potential through the game and its community. Taking the weights off and ascending.

That feeling is what’s behind at least some of this. And the fact that most competitors in the FGC strive for that feeling…

That alone might be part of why the FGC is so queer.

What homophobia costs

But it’s not all self-improvement and competition and anime shit that drives the FGC’s diversity. That diversity is also born out of practicality. It’s something that helps the FGC’s smallest scenes survive and that makes its largest ones more durable. It’s the stories — both good and bad — that prove this.

When I talk with Josh “Jaaahsh” Marcotte, he tells me a story that runs almost the direct reverse of Romolla’s. Josh is a gay man — and has been happily so for most of his life. He knew he was gay at a young age and he used games (particularly Nintendo titles) to forge connections all his life. (His intro to Smash Bros. 64 was playing with his straight brother and his intro to Melee was with his first long-term boyfriend.)

Josh got hooked on Smash during Brawl and sought out his local college tournament. He went in as a nobody and nearly came out as a top player.

“I did very well, I beat a lot of really reputable folks. There weren’t really rankings at the time. It was kind of unclear who was great, but I certainly wasn’t seeded to make it as far as I did.”

Josh sat in Losers Finals, guaranteeing him 3rd place, already having gone well past proving himself. “I sit down to play and […] the crowd starts loudly referring to my game plan using the long f-slur in a way that is somewhat ambiguous about whether they’re talking about me, or Olimar — who I used.”

“I was very confident in myself and proud and it was really weird to hear [that word] in that context, so I lost,” Josh recounts. “I went back to my dorm and I didn’t have an emotional reaction to it, I just very soberly said, ‘I’m not gonna do that anymore.’ ”

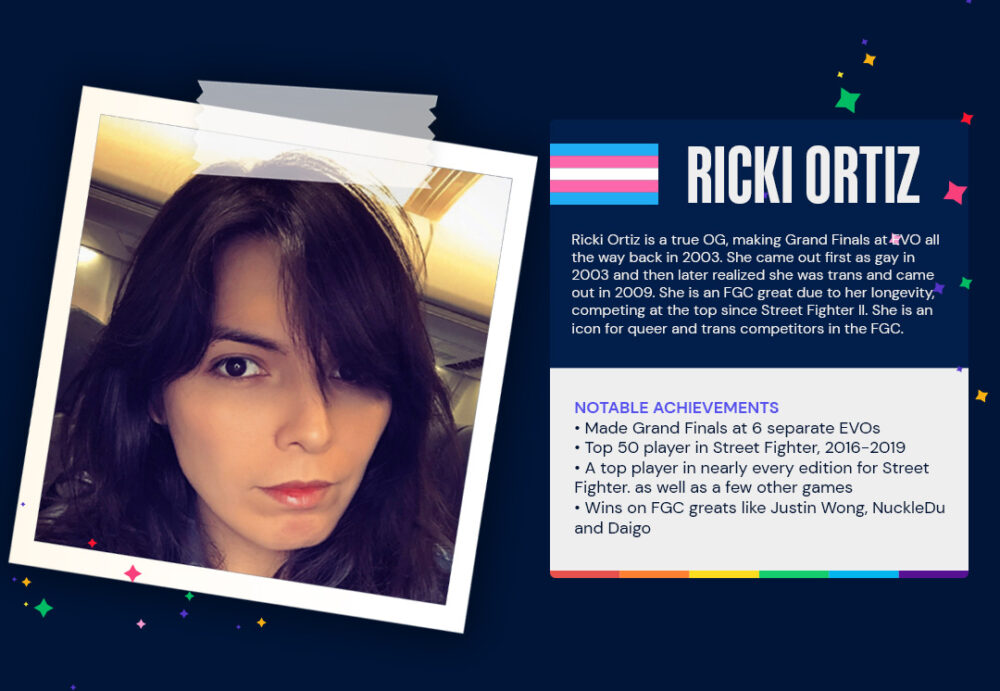

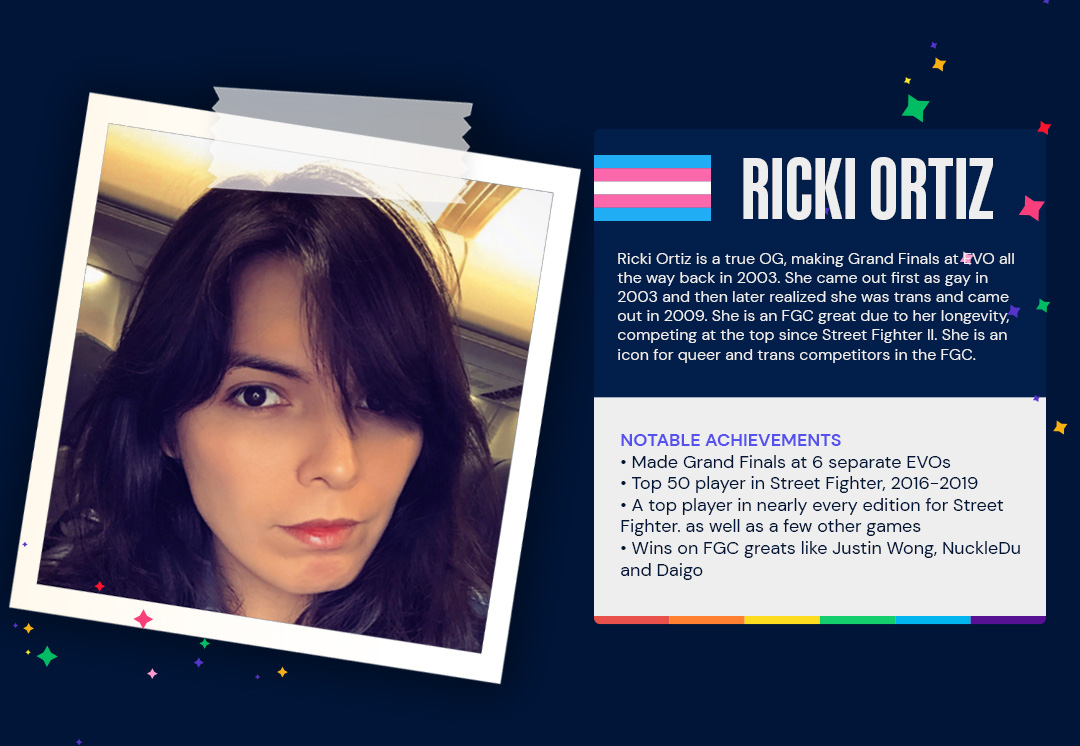

(Ricki Ortiz was one of the few queer fighting game players to rise to the top in the early days of the game. Her presence is something that Romolla, Dara, and Magi all referenced.)

Josh left the Brawl scene entirely after that, though he at least got a copy of Sims 2 for his trouble. (Which is ironic too, given how important The Sims is to queer gamers.) Josh notes that this was just how people talked in the Smash scene back then — but that didn’t mean he was obligated to endure it.

Josh didn’t need Brawl. But Brawl kinda needed people like Josh.

A year or two later, the Brawl community would slowly collapse and Smash in general would enter a dark age. Brawl (and Smash at large) struggled from a myriad of issues, but one of them was a lack of good tournament organizers and healthy leadership. These were things Josh absolutely could have provided — and that’s not speculation. When Smash 4 came around, Josh stepped back into the scene and he quickly became a lead tournament organizer (TO) for nearly every major event. (I went to the locals and regionals Josh ran in Minnesota, and I didn’t realize how spoiled I was until I moved and went to other locals.)

Would Josh have saved Brawl? Probably not by himself, but that’s not the point. The point is that any kind of bigotry or exclusion can have a cost in terms of talent. And when you operate in a niche — like even the biggest esports do, you can only afford so much. The Guilty Gear scene, especially in its early days, was so small that every player mattered.

Romolla recounts how a lot of technique videos in the West came from a Japanese trans player named Silva Hime. These videos were so crucial (really all knowledge was so crucial) that chasing out someone as actively helpful as Silva Hime would have been disastrous. This was even more the case for Guilty Gear Xrd (the prior title in the series), because of how every character had completely unique techniques and ways of approaching a match. If the best Sol Badguy player you knew was gay, then you needed to accept that and learn from them — or get rolled by Sol Badguy forever, as your punishment for being a bigot.

“For a lot of people, it was not worth being antagonistic or weird,” Romolla explains, “because it’s like, ‘I need this person to get better. I need this person to improve.’ In Xrd — it’s so funny to say this — but outside of a kind of early rough period, where not a lot people [understood queer identity] super, super much, it was never an issue. Somebody would say like, ‘I was uncomfortable with something. I didn’t like how you did this.’ And [Xrd players] took it to heart because they valued that community and that connection.”

The grassroots of fighting games

That community, that connection is so unique in part because of the very structure of the FGC. There is a unique locality and physicality to the FGC and Smash — and it’s those qualities that brought Dara, one of Smash Ultimate’s most successful commentators, into the scene and into a career.

“To me, the locality is why Smash is what it is,” Dara says. “The big streams the tens of thousands of viewers, none of that is what Smash is really about. Smash is about the absurdity that in every major city in this country [The US], as well as [in] many other countries, the fact that there is a different smash tournament in every city that is weekly.”

That locality is so baked into these scenes that “local” is a term for the small-scale weekly goes on in a city. The local is both so small and so natural that’s easy to overlook — but it’s important because it’s something that encourages people to be excellent to each other.

As Dara puts it, “You being at an in-person, weekly event, have the social pressures, to not be a piece of shit.”

The social pressure to not be a tool exists everywhere and there is a strong in-person element to something like a Counter-Strike LAN. But what the LAN lacks — and what Dara, Romolla, and Magi point to — are the friendlies or casuals. Basically, when most people enter the FGC and Smash, they enter as competitors. There are many branching paths — organizers, top players, content creators, artists — and this is something Josh and Dara both point to as helping the scene become diverse. But most people start as or become competitors. And whether or not they’re good at the game, they sit down and practice with other people in friendly or casual sessions.

“I’m trying to think about the LAN versus the local — and they’re such different concepts because LANs are such a spectator sport […] and there isn’t this culture of friendlies. […] We’re sitting down, we’re playing this game, and we’re physically next to each other and we see each other.”

When you enter any fighting game community there’s a certain parity, where everyone plays face-to-face, and so you share not only a space but a sense of humanity. In the online world, it’s easy enough to swap that humanity out for an image or idea of that person. At the local, it’s much harder.

It’s easy to be hateful as a keyboard warrior, where you can replace the shared humanity of another person with any image or idea you like. But when you’re there, sharing the same console, the same hobby and the same space, you also share a deeper sense of humanity.

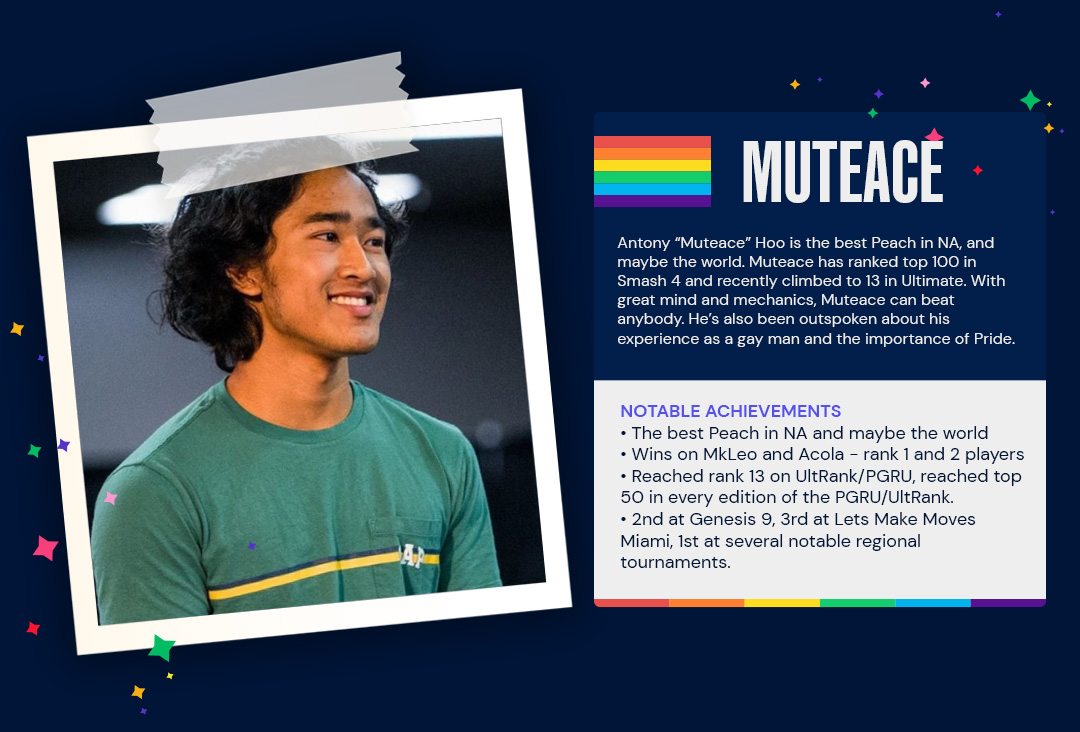

(Similar to Dara, Muteace was part of the younger Smash 4 generation that helped create a shift in the culture from the Brawl days.)

Additionally, online, it’s rare that people look for a sincere conversation, as much as they look to fire a deranged potshot in an imagined culture war. (Most algorithms encourage the latter, not the former). At the local, a lot of that shit falls away and in its place, real conversations emerge. Imperfect conversations, but helpful conversations all the same.

“On a local level, what I think helps is somebody getting talked to,” Dara says. “Normally what you have is, especially with, a younger kid who’s being weird and shit, they just get confronted by somebody telling them, ‘Hey, you’re gonna knock this off.’ That [conversation] spread out through every tournament throughout every scene throughout the country [mattered a lot].”

Not to mention, there are shades to “knock that shit off” that you can communicate much better in person. In online interactions, there’s not only an intense black-and-white feel to conversations and corrections, but there’s also a mad rush to get to a desired outcome before the conversation fades out of relevance. In real-life, meatspace communities, things usually move more slowly, people have more patience, and conversations and corrections have more nuance.

When Magi came out, she was the first trans person that most of her Louisiana scene had met. From the get-go, her scene welcomed her transition — but told her that there’d be a lot for them to learn. Magi knew that her local scene was ultimately friendly and had already welcomed other queer people, so she approached the situation with some light-heartedness.

“We didn’t want it to be super aggressive. I remember, in the very beginning I was pretty sympathetic towards a lot of people not knowing what a fucking trans person was. So I tried to make it not as confrontational. [What] we used to do [was]: if you misgendered me, you take a shot of alcohol. I was just like, let’s disarm this.”

Romolla adds that, for the Xrd community too, “there was no maliciousness. People were just unfamiliar with the concept. They’re just gamer bros. They’re just gamer dudes! They’re just like, ‘I want to play.’ ”

In Magi’s case, the lighthearted, gamer dude energy ended up coming back around in a really wholesome way, as she began to transition in earnest. “I remember when I went to the first tournament after I came out, I also showed up and presented how I actually wanted to. And people were popping off! Like, ‘Yo! Let’s go!!’ type of thing. It was awesome!”

Magi does stress that there was some outright homophobia or transphobia, and in this case, the response from her scene scaled to meet that. “If someone was being a dickhead about it, then we would also be more stern about it.”

A community needs leaders (and elders)

An important part of that sternness is that it can’t always come from young queer people like Dara or Magi. Leadership is what sets the tone. When Josh returned to the Smash scene in 2014, he helped set some of the stern lines that weren’t there in the Brawl days.

“At all passes, at every event, at all times I championed this idea of: you will respect the shit out of everybody. You will never, in my spaces, have the capacity to belittle someone’s humanity.” Josh’s tone radiates just how core this organizational tenet was for him. “I was vehement about that, talked to people when they crossed lines, and barred people from events when they continually crossed lines without any remorse.”

Magi, lays the same point out, but even more flatly. “We just started fucking banning people who are transphobic, who didn’t want to fucking stop being transphobic.”

“Like, if they wanted to die on that hill. We said okay. […] It did have a really heavy influence because I think things like that trickle down into the culture of the scene. Nowadays, it’s just intuitive as a result of a lot of those decisions.”

Even now, though, queer people are still a minority in most FGC scenes. For a minority to be protected that well, it took buy-in and change from the larger scene. A part of that change came from the general political landscape and improvements in LGBTQ+ rights. Josh (half-jokingly) gives credit to Hillary Duff, but more sincerely points to how LGBTQ+ issues like gay marriage became a highly visible fight during the 2010s and how that changed a lot of perspectives.

[embedded content]

(Hillary Duff’s “Don’t Say Gay” ad. It earned a lot of ridicule back in its time, but it did advance the conversation.)

Another part of the change came from both allies and elders. In the case of allies, it wasn’t grand changes of heart as much as it was people meeting queer members of the community and truly listening to their grievances. Melee commentator Bobby Scar was once legendary for using gay as an insult but over time, pushed hard for the scene to change that behavior. This kind of thing, Magi notes, sometimes has even more of an effect coming from allies than queer folk.

“I think people who are not queer […] do hear queer voices, but things make more sense to them whenever things are said by someone who is not queer, right? […] If someone who like, ‘isn’t biased towards queer people,’ because they’re not queer themselves is also in support of queer people, that has a more of an impact on people who are on the fence.”

For Magi, much of her journey was about allies. She was, far as we could both tell, the first major trans player in Melee’s history, so she relied a lot on the leaders in the local and national scene. This went so far that, while Magi was still in the closet to her family, she told commentators to misgender her on broadcast, so that her parents wouldn’t catch on.

But for Romolla and Dara, the journey was more about queer elders.

“Smash was actually instrumental towards me finding myself,” Dara explains. “Smash was my first actual real-life experience with a trans person. Having that kind of healthy exposure and talking [with her], that was really important to me, because I would have probably not met a trans person [for a long time otherwise].”

Romolla, who had known she was trans for years, also met the most vital trans mentors in her life via Guilty Gear. These mentors were ZenZen and Silva Hime, both top players themselves, who had not only gotten the scene to be more accepting of queer people but gotten Romolla to be more accepting of herself.

“Without Silva or ZenZen both being visible and talking with me, I probably wouldn’t have been as comfortable. I definitely came off a lot of trauma and they were very supportive, and helpful — and yeah, there’s a reason they’re still my best friends! They’ve done a lot of really good things for me and heavily encouraged me to be more true to myself, and by extension, way more happy.”

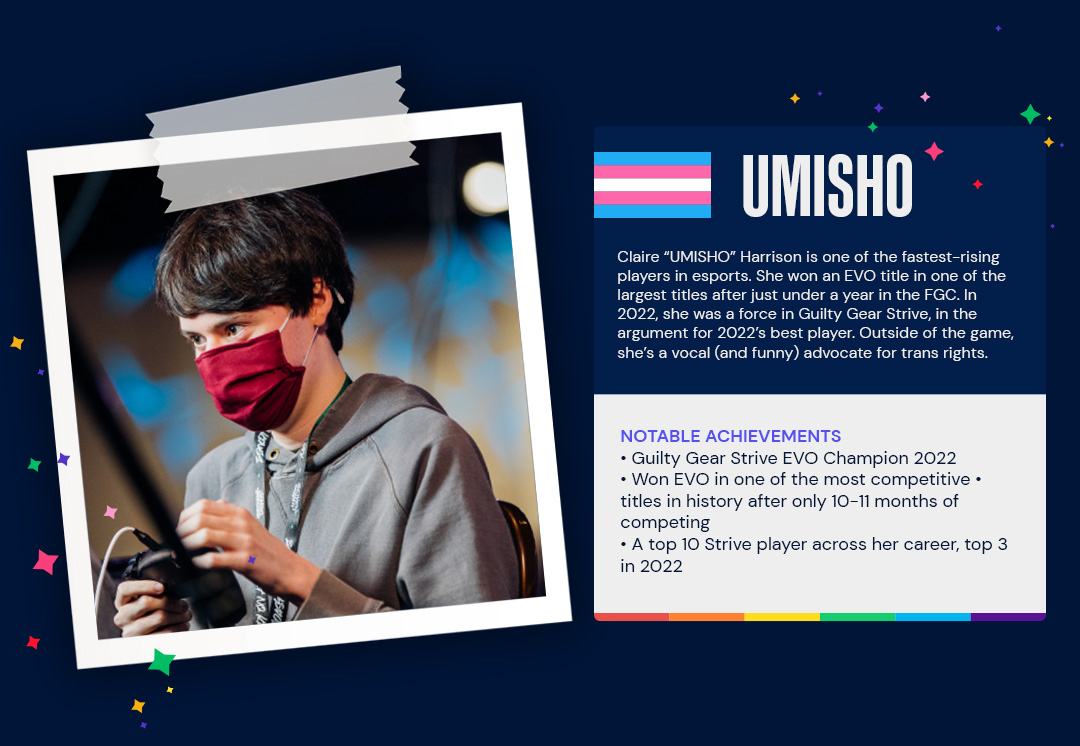

(Umish represents the true new guard of Guilty Gear.)

In Josh’s case, he was well aware that as soon as he became an organizer, he was also that elder in his own right. “I was the first visible queer person that [some Smash players] interacted with regularly and saw. My whole life was doing just fine, I was a good role model. I certainly know a lot of folks who recognized the kinship they felt with how I behaved in the world and how I experienced the world and how I expressed myself. […] I’m happy to have been that for the number of folks that I was that for.”

As time moves forward, Magi and Romolla are becoming mentors too. Neither competitor is anything close to old but both of them are now experienced and can lend that experience like ZenZen had. At a recent major tournament, Romolla even ran into a fan who used her to stream to help navigate being trans.

It’s a bit surreal for Romolla, who not long ago felt like a youngin in an aging Xrd scene, but it’s a source of pride. “It’s nice being able to support people and help them when [transitioning is] a pretty intimidating or scary thing to go through or you may not have space to process it or ask for help. So being able to support people in that way or help them is really, really nice to me and something I’m really proud of.”

Magi, who never quite had a ZenZen figure herself, greets it with unabashed enthusiasm. “One of the coolest perks is having a lot of people contact me and say, ‘You’re the first trans person I ever saw. And you were a very big impact in my life as a result.’ Like, that’s super sick, right? I fucking love that shit.”

Queer in all senses

Magi is right to love that shit. Taking off your own weight is empowering — helping others to do the same is even more than that. It’s creating space for queer people when it’s more needed now than ever as there’s been a major spike in anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment — especially towards trans people.

In times like these, Smash helps Magi keep steady. “I think for a lot of us and like a lot of people who are in those red states, like who are definitely on the brink of it. It’s so fucking stressful right now. I think the Smash scene, it’s just our retreat from the world for a little bit.”

As a gay man, Josh sees some familiarity in the talk used now to rile up anti-trans and anti-LGBT sentiment. The groomer rhetoric, while new to some, is something that he’s faced down before.

“I have constantly, since the dawn of me going to that first event, been incredibly cognizant of this perspective. I think it’s something that has always hung over me working with a community of folks of many different ages. As a gay man, there’s, I’ve always been worried about folks seeing younger folks at my events and what they must think of me as a result.”

In response, Josh has always taken extra steps to reach out to parents directly and talk to them more extensively than a straight TO might. He’s taken more steps to establish his credibility and background as a person, as well as to keep multiple lines of contact open for anyone feeling in danger. As the groomer talk resurfaces, Josh’s experience as a gay man is more vital than ever, and his experience tells him that rather than fall back, queer folk and their allies should gear up, challenge the homophobia, and continue the work of creating good community.

“What our job continues to be, with every new wave of player that comes in, [is] continuing to reassert our values as a community, continuing to reassert that these are safe spaces, continuing to reassert that all people are valid. […] We respect each other as people. And we do not denigrate others on the basis of any number of things, but very specifically here, queer identities and trans identities.”

For some parts of the fighting game community, there’s always going to be a desire to turn apolitical and turn away from all that work. There are always going to be questions about how all this relates to the game — why folks don’t keep a singular focus on the game. But to me, the whole point of the “community” in the FGC is to build that space where the weights can come off and where identity is respected enough that it really does not have to be a main focus. To allow as many competitors as possible, from as many backgrounds as possible, to compete and create and organize and lead and find their space.

To me, that’s what’s special about the FGC. That’s what makes the FGC queer — in all senses of the word.

Josh: “I know many, many of folk who say, ‘I’ll wear a skirt to a smash tournament, I won’t wear a skirt to the mall.”

Dara: “Smash was the first place where I was like, okay, I can identify and dress how I want,” Dara says. “That was, at that point in my life, the only place that I really had to do that.”

Magi: “Whenever I was uncertain about whether it was okay to be me, the Smash scene was the space to teach me that yes, yes it is.”

Romolla: “I was so comfortable presenting myself publicly in Strive because I was so comforted by the extra community, you know?”

Writer // Austin “Plyff” Ryan

Graphics // Brenda Cardoso

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.teamliquid.com/news/2023/06/30/why-is-the-fgc-so-queer

- 1

- 2014

- 2019

- 3rd

- 7

- 8

- a

- able

- About

- absolutely

- accepting

- Actively

- actual

- actually

- Ad

- adds

- advance

- after

- age

- agenda

- aggressive

- Aging

- ago

- Alcohol

- algorithms

- All

- allow

- alone

- already

- also

- always

- an

- and

- anime

- anime fighting games

- Another

- answer

- any

- anymore

- anyone

- Anything

- approaching

- ARE

- around

- Artists

- as

- aspects

- At

- attracts

- aware

- away

- back

- background

- backgrounds

- bad

- basis

- BE

- became

- because

- become

- becoming

- been

- before

- began

- beginning

- behind

- being

- besides

- BEST

- Better

- between

- beyond

- biased

- BIG

- Biggest

- Bit

- Bobby

- both

- broadcast

- broader

- brought

- build

- but

- by

- came

- CAN

- Capacity

- Career

- case

- casual

- Catch

- certain

- certainly

- challenge

- chance

- change

- changed

- changes

- character

- child

- City

- close

- cognizant

- collapse

- College

- come

- comes

- coming

- commentators

- communicate

- Communities

- community

- compete

- competition

- Competitive

- Competitor

- competitors

- completely

- concept

- concepts

- Conclusion

- confident

- connection

- Connections

- Console

- constantly

- contact

- content

- content creators

- context

- continually

- continue

- continues

- continuing

- contribute

- Conversation

- conversations

- Core

- corners

- Corrections

- cost

- could

- Counter-Strike

- countries

- country

- create

- Creating

- creator

- Creators

- credibility

- credit

- Credits

- crowd

- crucial

- Culture

- Current

- Danger

- Dark

- days

- decided

- decisions

- deeper

- definitely

- depth

- desire

- desired

- destroyed

- DID

- different

- difficult

- direct

- directly

- distance

- diverse

- Diversity

- do

- does

- doing

- don

- done

- dorm

- down

- drives

- During

- each

- Early

- earned

- easy

- edition

- Effect

- effort

- element

- embedded

- emerge

- Emotional

- empowering

- encourage

- encouraged

- encourages

- energy

- enough

- Enter

- enthusiasm

- entirely

- especially

- esports

- establish

- even

- Event

- events

- EVER

- Every

- everyone

- everything

- Everywhere

- EVO

- experience

- experienced

- explains

- exposure

- expressed

- expression

- extension

- extensively

- faced

- fact

- fall

- familiarity

- family

- fan

- far

- feel

- few

- FGC

- fight

- Fighting

- Fighting game

- Fighting Game Community

- Fighting Games

- Figure

- finale

- find

- finding

- fine

- Fire

- First

- first place

- Focus

- For

- forever

- forge

- Former

- Forward

- four

- friendly

- from

- full

- funny

- game

- Game tournaments

- gamer

- Games

- Gaming

- Gear

- General

- generation.

- Get

- getting

- GG

- given

- gives

- go

- goes

- going

- gone

- good

- grassroots

- great

- guard

- Guilty Gear

- had

- hand

- happy

- Hard

- harder

- has

- Have

- having

- he

- Headlines

- hear

- heart

- heavily

- heavy

- help

- helped

- helpful

- helping

- helps

- her

- here

- higher

- highly

- him

- his

- history

- How

- HTTPS

- Humanity

- i

- idea

- identify

- identities

- Identity

- if

- illness

- image

- imagination

- imagined

- Impact

- important

- improve

- Improved

- improvements

- in

- Including

- incredibly

- influence

- instrumental

- Insult

- Integral

- interactions

- intimidating

- into

- intuitive

- Is

- isn

- issue

- issues

- IT

- ITS

- Japanese

- Job

- journey

- jpg

- just

- keep

- Keyboard

- kind

- know

- knowledge

- known

- lack

- LAN

- landscape

- large

- larger

- largest

- later

- Lays

- lead

- leaders

- Leadership

- LEARN

- least

- leave

- left

- Legendary

- lend

- Level

- Life

- like

- lines

- Liquid

- Listening

- Little

- ll

- local

- locked

- Long

- long-term

- Look

- lost

- lot

- Louisiana

- love

- loved

- made

- main

- major

- Major Tournament

- make

- MAKES

- man

- manager

- many

- Match

- matter

- May

- me

- mean

- meet

- Meeting

- Melee

- Members

- met

- might

- minnesota

- minority

- mode

- model

- moments

- more

- most

- move

- moved

- much

- multiple

- must

- my

- named

- National

- Natural

- navigate

- nearly

- need

- needed

- needs

- never

- New

- Newest

- Next

- Nice

- Niche

- Nintendo

- no

- not

- notable

- notes

- now

- number

- of

- off

- often

- Okay

- Old

- on

- once

- One

- ones

- online

- only

- open

- operate

- or

- organizers

- Other

- Others

- otherwise

- our

- out

- Outcome

- outside

- over

- own

- parents

- part

- particularly

- parts

- passes

- passion

- Past

- patience

- People

- perfect

- period

- perks

- perspective

- perspectives

- piece

- place

- plan

- plato

- plato data intelligence

- platodata

- platogaming

- play

- player

- players

- Playing

- plays

- Point

- Points

- political

- Popular

- possible

- potential

- practice

- presence

- presented

- pressure

- prestigious

- pretty

- prior

- probably

- Process

- Pros

- protected

- proud

- prove

- provided

- publicly

- pursuit

- pushed

- question

- questions

- quickly

- quite

- rankings

- Rare

- rather

- RE

- reach

- reaction

- Real

- realize

- really

- reason

- recent

- recognized

- red

- regional

- regularly

- relevance

- Remember

- replace

- representation

- represents

- reputable

- respect

- respected

- response

- result

- Retreat

- return

- reverse

- right

- rights

- rise

- role

- rolled

- running

- runs

- rush

- s

- safe

- Said

- same

- save

- saw

- say

- saying

- says

- scene

- scenes

- see

- seeing

- seen

- sees

- sense

- sentiment

- Series

- sessions

- set

- sets

- Share

- shared

- sharing

- she

- shift

- shot

- should

- showed

- side

- silva

- similar

- sims

- since

- Sit

- Sitting

- situation

- small

- Smash

- Smash Bros

- So

- so Far

- Social

- SOL

- some

- someone

- something

- Soon

- sought

- source

- Space

- spaces

- special

- specifically

- spike

- Sport

- spread

- start

- started

- States

- steady

- Steps

- still

- stop

- Stories

- Story

- straight

- stream

- streams

- stress

- strive

- strong

- structure

- successful

- such

- Summit

- super

- support

- support people

- supportive

- sure

- survive

- swap

- swiftly

- tag

- Take

- taken

- taking

- Talent

- talk

- talking

- TeamLiquid

- techniques

- tell

- tells

- tens

- term

- terms

- than

- that

- The

- The Game

- The Sims

- the world

- their

- Them

- themselves

- then

- there

- These

- they

- thing

- things

- think

- this

- those

- though

- thousands

- Through

- Throughout

- tier

- tiktok

- time

- times

- Title

- titles

- to

- Ton

- too

- took

- tool

- top

- tournament

- Tournaments

- towards

- traditionally

- transition

- transitioning

- tried

- true

- truly

- turn

- turned

- two

- type

- ultimate

- ultimately

- Uncertain

- unclear

- under

- understanding

- understood

- unfamiliar

- unique

- Unreal

- until

- unusual

- up

- us

- used

- using

- usually

- valued

- values

- ve

- Versus

- very

- via

- victory

- Videos

- viewers

- vital

- VOICES

- want

- wanted

- war

- Warrior

- was

- wasn

- Wave

- way

- ways

- we

- week

- weekly

- welcomed

- well

- went

- were

- West

- What

- when

- whenever

- where

- whether

- while

- WHO

- whole

- why

- wider

- will

- with

- without

- Work

- working

- world

- worth

- would

- wrong

- year

- years

- yes

- yet

- you

- young

- your

- youtube

- zephyrnet